During the exhibition the gallery is closed, no. 2 When You Believe

The lobby (via SculptureCenter security cameras)

Editorial

Art without people

There are thousands of artworks currently on view in museums that no one goes to. Paintings and photographs on walls, sculptures on plinths and floors, installations immersive and not, videos, films, sounds, etc. These works are joined by millions of others left in climate controlled on- and offshore storage, soft or hard packed, in crates, on shelves, and in drawers. Considering the all-too-familiar Duchampian maxim that the viewer completes the work of art, we have too many works that, in the absence of viewers, are left incomplete. This incomplete art is art without value.

If we consider Duchamp’s equation, we realize that the value of a work of art is created by people, by those who pay to fill the galleries of museums, and lend their eyeballs to objects and images, and who, by doing so, evaluate what they encounter. Value is created by the labor of viewership. It is the presence of bodies in a space, in front of and around works of art, that sustains a field that more often than not extracts meaning from interiority and imagines a network of professionals and connoisseurs as appraisers. This is not unlike other spheres of contemporary culture and, more broadly, human activity. The application of the human body, its feelings, and its thoughts to an object, image, or commodity is often what grants it its value. Diedrich Diederichsen applied the labor theory of value to art production by claiming that the total time an artist spends in the art world (from academy to bars to openings, etc.), making art or not, is artistic labor and generates value. To this we might add that once the work is made, it requires bodies. These bodies could congregate around it at the same time, or over a decade or millennia. The value of the work – financial, symbolic, or otherwise – could spike and plateau, or decrease, or it could gradually increase over time as more bodies gather around it and more minds carry its memory, talk about it in public or private, replicate it, etc. Questions of expertise, populism, and management of scarcity aside, any kind of cultural product requires the user, viewer, or consumer to complete the cycle of value production.

In a work of art, the artistic work and that of the viewer/audiences converge. If the artist’s work includes all, or almost all areas of their life, their relationship with the totality of the everyday differs from the regulated time of labor. Similarly, the work of art reaches its constituents in their time out of labor. An artwork generates a relationship with time that contrasts the calendar time that serves accumulation. A work of art expands clock time, deregulates it and desynchronizes the temporality of human experience from that of labor time. If the artist’s primary material is bare time, uncalendared time, that is manifested in the time of the work, in the encounter with a work of art the divergent, disrupting, perverted, deviating, expanded temporalities of the work and its viewer are synchronized. Art therefore works against the clock of globally incorporated machine time. As opposed to the artwork, the culture industry aims to regulate time out of labor as designated leisure time and to synchronize it with the clock.

Now, in times when fully installed exhibitions in public and private art spaces remain closed, it is solely the eyeballs, instead of bodies, that institutions are vying for. Public relations are inundating distanced social platforms, strategizing on how to make their clients visible to the sequestered, cabin fevered audiences and to fill their time. Clickbaiting is institutionally mandated and hypervisibility is prescribed for organizational relevance and fear of digital obscurity. If the jpeg was the mp3 for visual art, quarantine is its Napster moment. But unlike recorded music, contemporary art does not maintain its intrinsic qualities through digital transfiguration, at least not immediately. The crisis of quarantine creates another crisis for the field: the crisis of value. While PR and marketing agencies can equate the value of their work with stats, institutions lose the value of space, time, and labor and risk being replaced by applications and platforms. Hypervisibility equals invisibility in the endless scroll. If we follow the example of music, it is not only institutions that will lose relevance. The primary burden falls on artists as their works become just an instance in the eternal digital flow. This is not to make a case for digital naivete, as contemporary art has used and metabolized the internet as an integral part of its ecology. From e-flux to Contemporary Art Daily, vdrome and other platforms, the art world is alive and well on the web. However, even the most digitally native works of art still often rely on bodies in a space for their completion. The current situation might change that, as more artworks and attempts to replicate the experience of art migrate online. VR could replicate the exhibition experience in the living room. While the current cloud transition prioritizes the retinal experience above all, it also provides extra-institutional access to works of art. But to migrate artworks that were made to be experienced in situ to online viewing rooms overnight is only in the service of an economy of visibility that serves the algorithmic patterns of platforms that mine human intelligence and labor to generate IPO value. All of a sudden, it appears that the work of artists, institutions, and viewers are now all in the service of speculative evaluation of web-based platforms, facilitated via marketing schemes that harvest optical engagement with content into quantifiable metrics of labor time, time of maximizing corporate yields.

Perhaps in anticipation of this wholesale transfer of institutional content to the data industry, artist Bahar Nourizadeh in collaboration with Mahan Moalemi created CAD Conspiracy (2019). The work fed 60,000 installation shots collected from contemporaryartdaily.com into the machine learning framework of a generative adversarial network (GAN). While “learning” from these images over the course of the exhibition, the software generated its own “new” installation shots. The work shows how a wholesale migration into modes of online display could conflate the operations of the contemporary art institution with those of processing software that generate “autonomous” content and opt for a technocratic machine time over the divergent temporality of art.

As Mark Fisher said, all that is solid melts into PR, and art becomes a decoy for startup cognitive data collection. Art is long and public attention is often short, wrote Gary Indiana in his first column for the Village Voice. Marketing and public relations regulate and yield attention and render the work of viewership into unpaid labor of instant cultural consumption. But the shelf life of art does not follow the immediate response of the media: it is prescient and reflective, oneiric and haunting, subsequent antecedent; it creates its own constituents, and they in response culminate it. To render art into swiped online content is to unmake it into information that machines process for other machines that take our time and fill it up with theirs. Art creates time, it does not take it away.

There is no art left without people.

- Sohrab Mohebbi

When You Believe

This dispatch jumps off from the idea of disbelief, an organizing thematic for this year’s In Practice open call exhibition. Some of us are swinging sharply between poles of belief and doubt at present, but incredulity may have characterized our outlooks on our social, political, and professional lives for a while now. In addition to a PDF of our new exhibition publication, we include here a selection of materials that broadly circle this idea.

New Exhibition Publication

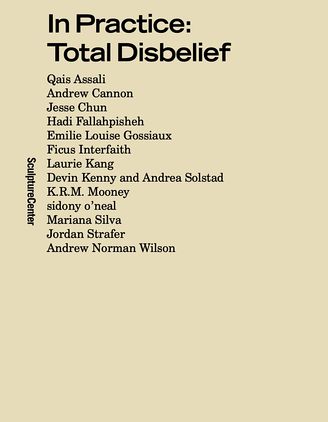

The catalog for In Practice: Total Disbelief includes exhibition documentation, a new essay by Kyle Dancewicz, the exhibition’s curator, and entries for each included artist or artist team. Across these artists’ varied practices, Total Disbelief considers how doubt productively pervades both artistic positions and social life. In Practice is SculptureCenter’s annual open call exhibition, and the call for the 2021 exhibition is now open on our website.

In Practice: Total Disbelief

SculptureCenter, 2020

Related Materials: Preciado, Absalon, Strafer, Kierkegaard

Don’t produce anything. Change your sex. Become your professor’s teacher. Be the disciple of your student. Be your leader’s lover. Be your dog’s pet. Anything that walks on two legs is an enemy. (Read “Pack Up Your Things” from Paul B. Preciado’s An Apartment on Uranus.)

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, artist Absalon (1964-1993) made what he referred to as “cells” -- sculptural habitats streamlined for living an austere but transportable life. Solutions (1992) is a case study of everyday activities undertaken in one of Absalon’s cells, which he saw as both a psychic elaboration of his inner life and a protective shell against the sociopolitical constructs of the outside world. “I would like to create my own setting,” he said, “and belong to nothing else.”

Jordan Strafer’s PEP (Process Entanglement Procedure), technically still “on view” in In Practice: Total Disbelief, is a “horror-memoir” about the fraught collision between victimhood and the spectacle of public testimony. Another way to describe this, and some of Strafer’s other videos (available on her Vimeo page), is that the public’s interests rarely align with the public interest.

If you want to know what Kierkegaard thought about doubt, look no further.

Links: From the web

Artist Paul Maheke on the real stakes of the COVID-19 crisis and the false hope of visibility in the present moment: “The Year I Stopped Making Art” on Documentations (and a link to a UK QTIBIPOC Emergency Relief & Hardship Fund via the artist’s website).

Shelter In Space, a short series on leaving the world behind for now and finding peace in orbit by Mary Potter and Nick Zeig-Owens.

“A bad joke in a bad time”: Shabahang Tayyari’s video Not titled yet (Bakintash Abdu Jamal) (2018), from a larger project about a fictional extremist and his wife, who loves Metal.

Spectacle: A Portrait of Stuart Sherman, a documentary about artist Stuart Sherman (1945-2001) and his perplexing performance works with everyday objects, often pulled from a suitcase and presented on a folding card table.

Andrew Norman Wilson’s course syllabi for The Vampire Squid from Hell Club and The Theater of Truth.

“Skeletal Readings,” a meditation by artist Asher Hartman followed by a conversation with critic Rossen Ventzislavov.

For feeling both insecure and indestructible: Sara Magenheimer’s Safe (2020)

Tune In

Moriah Evans’ 222 Ways to Get Inside Yourself (Fridays at 12pm EST on @___homecooking___)

Guided Meditation with Andrew Cuomo (via Avery Singer)

Two Lizards (Orian Barki and Meriem Bennani)

Quarantine Mix (by Marie Karlberg)

The Death Panel (Podcast)

Augmenting the Virtual with Ajay Kurian

Remarkable Rabbits (From Nature on PBS)

Taxi zum Klo (1981)

Postscript

Email response from Alex Reynolds re: Bare Time

Resources

Inpatient Press Remote Grants

List of Arts Resources consolidated by Creative Capital