Conversation between Curators of 74 million million million tons

74 million million million tons

Ruba Katrib and Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Ruba Katrib: When we started working on the exhibition 74 million million million tons, we had a general concept for what we wanted to do and in our first conversations began plotting out a direction. You hadn’t curated a show before and it was a new experience for you to work in an institutional context in a curatorial capacity, and this was part of the process.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan: Definitely.

RK: We started by looking at a few artists’ practices we wanted to bring forth. You had just been in an exhibition and were interested in some of the other artists who are directly intervening in material, not only speaking metaphorically about something that’s happening. We agreed that this was a mode of working we wanted to examine. By looking at practices that engage direct intervention and produce knowledge, information, and material rather than a more ambiguous referencing.

LAH: I was feeling a bit frustrated with the ways in which research-based practice was solidifying into works and how it was becoming formulaic in its relationship to form. It was, “I have a body of research, and I now have to think about how I can very smartly transform elements of this research into certain kinds of gestures, either in video or another material.” The logic of these kinds of productions was becoming increasingly rigid and less and less accessible to the viewer, who had to look at the work in terms of what the research was and how it was constituted.

I started wondering if there were another model, where the thing that is being examined could itself become manifest. How are artists thinking differently, outside the conventions of a classic research-based practice by, as you say, directly intervening in the thing, producing the thing? Like Sean Raspet’s project Nonfood, which is also a start-up he founded through working with flavors from an artistic perspective to create an actual product. Or Shadi Habib Allah’s 2g network, which he built to uncode or de-decode Bedouin smuggler networks, using their very materials and practices: through this intervention, new aspects and narratives of colonialism and the violence of national borders emerge. Or Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s virtual reality pornography work, where she proposes how to instrumentally contest something. She doesn’t just point a finger at the activity or critique it from a distance, but enters the system itself to produce, through virtual reality, a moment that could actually challenge the very thing you as a viewer are scrutinizing and momentarily inhabiting.

These ideas seem to be shifting the framework and direction of research-based practice.

RK: Our challenge was to make an exhibition that articulates a changed working methodology. Research-based practice has been associated with, as you say, the disconnect between the form and the thing, but also, in a basic sense, documentation and information––finding something that happened and then a way to represent it. What emerged was a shift in the modes of representation of research; artists are now producing new representational models or forms for very complex histories, moments, and events. This distinction was key in our conception of the show. There are plenty of artists who have delved into an archive and produced material from it that we didn’t want to work with on this occasion because this type of practice has been seen so often. We looked instead at artists whose work occupies a liminal space where it can be considered in a number of ways. We were interested in connecting them through their shared process of producing new forms of representation within the art context and beyond. As with Sean, who was making an artwork but also a real product.

In her overall project, Susan Schuppli engages in long-term, ongoing investigations. She has plenty of sources to work with, mostly existing materials she’s collected to look at how they work as images. For two new bodies of work, titled Nature Represents Itself and Slick Images, she put together different images sourced from private and commercial interests, alongside a new CGI animation and other elements, to create a new type of image that represents the events of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Another example is Daniel R. Small’s Animus Mneme installation, where he is researching things from the past (the Antikythera mechanism), the present (lifeloggers and new efforts to upload human consciousness), and the future (AI technologies in development). He isn’t creating an archival document but activating specific historical materials with current manifestations and potential future uses or implications. He has made molds of fragments of the Antikythera mechanism, which is an ancient computer that was found in a Greek shipwreck from the first century bce, and cast them in Aerogel, a relatively new, lightweight, airtight material that’s used for, among other things, spacecraft insulation. This technology has applications for other kinds of ships. Spacecraft versus sea vessels. He links ancient history to the future.

These are interesting ways in which artists are activating the narratives around events and materials they’re researching in order to propose new forms whose implications can be thought about from many different angles. All kinds of institutional questions came up during the exhibition planning, such as the boundaries of legality: these events and entities haven’t been regulated or administrated, and are being sorted out in a process that remains in the works.

LAH: Coming back to the question of methodology, Daniel’s work weirdly represents both the antithesis of what the show is trying to do and exactly what it is trying to do. What I mean is that if it weren’t for certain decisions he makes, his art-making process would be exactly the one we were trying to avoid, because it does exist in a relation to form produced through research that is conceptualized on every level and that sometimes occludes the visitor’s ability to understand or access the thing. However, why I think it’s perfect for the show, is that he’s trying to make a world. Basically, he’s creating a narrative that scales, as you say, from a deep past to the future, and in that sense he’s refusing familiar historical narratives. He’s not operating like the research-based artists who expose gaps within history or pieces missing from the archives. He’s writing a grand futuristic narrative about a collection of objects that are inseparable from one another and from the world they make. You can’t detach the Antikythera mechanism from the Aerogel, the robot, Bina48, or lifelogging. Although each of them could be independent projects in and of themselves, his work is to amass them to form a strange world in which they all meet and look at one another. That’s a very strong provocation, statement, or representation of the world that artists can make.

RK: He’s using multiple materials and sources, not diving into one history and saying, “Can you believe it?!” It’s more that he’s creating a line through different histories, materials, and geographical locations to show how they’re related, and unrelated, and to make a proposal by means of the world that he creates. He’s deliberately doing this through art, which is something that concerns all the artists represented. They consider how their subjectivity as artists produces this material. That’s something distinct from a lot of research-based work. Here the artist isn’t presenting as a neutral observer or researcher, but has a subjective position in relation to the material.

What does the language of art bring to this type of work? Susan, who is also an academic, pieces together material to create a new mode of representation that is specific to art and to what art can do. Carolina Fusilier, the one painter in this show, creates worlds sourced from imagery that reveals internal components, not only of the image but also of what it depicts––often watches and other mechanisms. An internal space is unpeeled, which can happen only through her painting process.

LAH: Carolina is a really good example. For me, where she holds strong to our initial exhibition concept and thinking is in representing, among all that we’re trying to communicate, the idea of a system of observation the artists enter. In a way, they care about the way things look as they seek to analyze them and understand their potential, even if by simply reproducing them. These are often things at the very edge, things people don’t notice or care about anymore, or perhaps their internal functioning doesn’t make sense. Maybe people are happy to have an elusive relation to the material functioning of objects around them, like our relation to the internet for example. To describe the internet we use immaterial terms like “ethernet” or the “cloud,” in fact it’s highly material. Sometimes, those artists who refuse the immateriality of things because their visual language is material (paint for Carolina) actually return these things to their material functions, their cogs, their inner workings. Through the intensity of her observations, she renders these machines visible in ways that amplify our relationship to the objects under scrutiny.

RK: As we assembled the show, we came up with these ten artists, knowing that something they were working on was related to these issues. Maybe not all of their practices were relevant in their entirety, but there was a line in their work that we were looking at and interested in. We invited them to come together based on the affinity of their methodologies. Something that was compelling in our conversations about the show is that the ideas come through the specific works that the artists brought to it, which operate in a very distinct manner. The exhibition framework allows for these types of research-based practices to enter a new mode of representation. By hinging the show’s overarching meaning on the depth and content of the artists’ works and the subjects they’re addressing, we were able to articulate certain themes while discovering a lot of interesting correlations we hadn’t anticipated.

An instance of this are the parallels between Nicholas Mangan’s and Daniel’s work. Demonstrating the connection of Earth-produced technologies to the universe at large, they both take their research from the ancient past to the future, and from the earthly to the galactic. Nicholas looks at solar energy through Aztec cosmologies and energy-harvesting technologies, and correlates them with mechanisms of currency and value as well as global events. Daniel looks at people in the Transhumanist Movement who send out their digital information and presumably their identities into space from satellites, and also links ancient cosmologies to these new technologies. George Awde, Hiwa K, Sidsel, and Shadi look at surveillance technologies and rights over the body, communication, and movement. Within the exhibition there are multiple ways of examining and representing similar phenomena.

LAH: By avoiding and refusing some of the conventions that have now been laid bare about research-based practice and finding new ways in which such practice can produce its own kind of knowledge, thinking, and relation to the art object and to the viewer, we have ended up with a group of artists who are joined not only by methodology but also by an earnest desire to arrive at an answer and not to only put things into question. For a lot of the works in the exhibition, you don’t need to know a lot about the artist’s research. They also work on a formal and conceptual level, since the thing and the thing being researched are one and the same. This earnest effort to render and reach the world in an unexpected way returns you to the notion of the eccentricity of artists. I’ve talked about this with Carolina––her obsession with machines particularizes her work––and Hong-Kai Wang really does believe in “clairaudience,” which is not just an artistic strategy, but a means, she believes, to make other modes of historical access to the history of colonialism in Taiwan redundant and ineffectual. Events persist in the blind spot of history despite the circulation of information. She chooses to use song-making as a strategy for telling this history in a way that can be heard. It’s almost absurd, but it is not ironic. She insists that this is a practice of epistemology, though it doesn’t make sense according to the received understanding of how epistemology works. Earnest insistence runs throughout the exhibition, in one way or another, and you don’t see a lot of irony. Rather, humor in the show might come from the artists’ eccentricity, their obsession or its announcement of things that may seem impossible but are rendered as credible options for history-making and the production of narrative and knowledge.

RK: All the artists in the exhibition are very much engaged in research in the present moment rather than showing archival materials documenting research of the past. In an ongoing process, Hong-Kai brings new layers to a partially lost part of colonial history. The narrative adapts and changes each time and place she does her workshops. The workshop is a methodology for making and remaking this history, sorting it out in the present

This is the case with Hiwa as well; his film A View From Above has open-endedness and ambiguity, but it nonetheless operates as a valid representation of the refugee narrative in Europe. It is a valid document. In replicating their subjects, all the artists produce valid documents that are useful and incisive, that provide a certain kind of information that reflects the situations they are imbedded in, without relying on definitive statements.

Most of the artists in the show are exposing networks. They bring to light the process through which something is made or concealed, for its contemporary relevance and its future significance. There is a sense that these histories and these works are not resolved at all. In their lack of resolution they differ from the archival elements in more traditional research-based practices. Because there is something investigatory and provisional about their making, their forms, materials, and manifestations as art are key to their meaning. They are unfinished narratives with the artists imbedded in them.

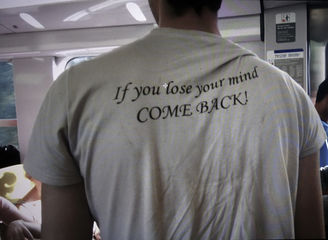

LAH: What you say about Hiwa is right, that even though his script has a kind of familiar though indeterminate framework, it’s an almost utilitarian idea of art’s open-ended interpretive possibilities. In a sense, there’s no other way to tell that story, because there’s a fictional world that the asylum seeker must endlessly devise. It relates to a careful way of elaborating biographical stories without completely exposing the methodologies by which asylum seekers navigate very tricky bureaucratic territories. What’s interesting here is that even these indeterminate poetics, the open-ended hermeneutics of art and the play with fiction and reality, are extremely utilitarian. It is a method that is useful for gaining access to people’s narratives that would otherwise negatively expose asylum seekers’ ways of navigating the legal terrain. It’s also a very poetic work, but the poetics are mobilized keenly and precisely so that you can feel the absurdity of this situation without exposing individuals who are forced to play within this political theater.

RK: The art of it allows the artist to disclose certain things and to conceal others. This aspect reveals the urgency of many of the subjects that the artists are implicated with, as collaborators and as subjects themselves. They are active producers, in a way, of the realms they are exploring. And the full story cannot be told, for many reasons: George and Shadi can’t fully disclose what they’re talking about. To do that would not only expose their subjects, but themselves. Through art, they are able to speak to these networks that are partially concealed, or about concealment, in a safe way. The idea of surveillance and the police state emerges in the exhibition, but the methodology of art circumvents the vulnerability that would result from fully disclosing what is being depicted.

LAH: In a way, they’re using the history of art’s relationship to, not necessarily fiction, but certainly artifice, using the artifice of art to paradoxically access the truth of specific events. This is done to amazing effect in George’s work, where graphite and gum arabic render his prints as something between drawing and photograph. He’s talking about things that you shouldn’t document or photograph because it would make you into a voyeur at secret orgies; yet to see them, and to see them through the lens of their invisibility, he uses the language of art in a way that is really smart. It folds back into artifice, but does so in order to reveal. A bit like Hiwa. Effectively mobilizing artifice is something that quite a few of the artists do for the purpose of shielding themselves. Because they’re often so implicated in their works, they have to protect themselves, and others.

RK: The thin line between fiction and evidence creates an ambiguity that allows artists to announce themselves in more than one manner. That’s why the notion of representation or future interpretation is central, because they’re not demanding that this work be considered one way or another. We know that the discomfort we feel correlates to something real, but we can’t resolve it. We accept that a veil of artifice or art has been created to protect the content, the material, and the people. Artists use certain methods of documentation and representation to reveal aspects of their subject, while also both concealing and drawing attention to what can’t yet be communicated or understood.