Lydia Ourahmane’s works often begin as large, open-ended propositions that find the edges of possibility within the political, environmental, and metaphysical conditions in which she operates. Tassili is an engagement with a remote desert, how and why one travels there, and the conditions of image production. Specifically it is about Tassili n’Ajjer, a largely inaccessible plateau near the border between southeastern Algeria and Libya. After a labored administrative process, Ourahmane and a group of collaborators traveled on foot through this region to produce a new moving image work, also titled Tassili, and to gather scans that later informed a new sculpture. These works and the political positions they represent comprise her exhibition at SculptureCenter.

Tassili n’Ajjer is host to thousands of prehistoric engravings and cave paintings that describe the transformation of life in the Sahara over thousands of years. The earliest appeared between 8,000 and 6,000 BCE. Across a network of caves, scenes of conflict and ritual submit to a drastically altered ecological landscape, once a fertile “bed of rivers,” as the translation of its name implies, and now an arid and inhospitable expanse of desert. Ourahmane’s film subsumes an encounter with a hypnotic array of this imagery – of ancient demons, extraterrestrials, and lost rivers and forests – while moving through a place that both collapses and measures the severity of time.

The oldest period of rock art of the Central Sahara is referred to as Kel Essuf. Essuf is a term used by the Tuareg people to refer to the desert wilderness, or to a sense of the unknowable – as an internal, psychological state, or in reference to the demon figures that appear in the drawings of the later Round Head Period, before depictions of animal husbandry and daily life appeared in following centuries. For Ourahmane, making a film is a pretense to engage with the spiritual dimensions of the plateau – a place marked by depictions of ancient rites that offer a long view of a relationship between people and the environment. Traveling in the desert is a way to interrogate questions around belief and trust, two evolving dynamics in her recent work, and what it means to physically put oneself in a space where one cannot navigate or survive without acquiescing to a radically different relationship to time and place.

Her project also poses a number of immediate questions, the first of which is whether or not this kind of image making – retreading paths of colonial-era archaeology and relying on local knowledge to support intellectual, spiritual and artistic objectives – is a neocolonial endeavor, even when undertaken by one whose perspective and personal experience reflect a sharp and critical attention to related legacies of colonial oppression. These are enduring concerns in Ourahmane’s recent work of and about Algeria, where she was born in 1992.

Tassili both obscures and heightens the contradictions of Ourahmane’s artistic and political position. The film itself is vibrant and seductive. Extended passages shot in first-person perspective traverse a striking landscape at walking pace, with footage edited together across days and nights. Ourahmane combines these point-of-view shots with seemingly static footage, night vision recordings, and sequences transferred from 16mm film.

A roughly forty-five minute edit of this seemingly uninhibited imagery conceals the conditions that both enable and control its gaze. To travel in Tassili n’Ajjer is to perform a strict choreography of resource management and walking routes that determine what can be perceived under extreme limitations of climate and physical endurance. These movements are in turn organized by Tuareg guides who rely on protocols of mutual trust and accountability to make safe passage across the plateau, which is sustained by a single source of water. In effect, one can only film where one can walk, with no chance to backtrack or act beyond the present moment and location.

By some accounts, Ourahmane’s effort to travel into the desert with extensive film equipment represents an impressive bureaucratic feat, a credit to the cultural legacy of the region, and a potentially critical relationship to the Algerian government’s management of this territory, its people, and its history. Ourahmane’s guides, for example, were born on the plateau but displaced by government officials in the 1980s; now they rearticulate or perform their relationship to their previous territories by escorting groups there. In another light, Ourahmane’s undertaking can be criticized as an absurd pilgrimage not far from tourism, funded by international cultural institutions, and mobilizing a local infrastructure of previously nomadic guides in support of a group of foreigners, who are typically forbidden from accessing Tassili n’Ajjer — and all of this for the sake of producing hyper-detailed imagery of a place that has resisted representation for years. Further, the film is scored as a four-part exquisite corpse by four composers, none of whom traveled to Tassili. Ourahmane’s invitation to these close friends and collaborators puts further stress on the artist’s own use of images of Tassili n’Ajjer and how wide its purview might stretch. The result is a set of divergent sonic approaches to the work’s imagery and varying degrees of compliance with the structures suggested by Ourahmane’s video editing, opening the work to another layer of ambient intervention.

Foreign depictions of Tassili n’Ajjer have a long history. Notably, the “Tassili frescoes” were conveniently “discovered” and illuminated by state-sponsored French archaeologist Henri Lhote immediately after oil deposits were found in the area in 1956, during the Algerian War of Independence. Lhote’s research methods subsequently damaged many of the drawings while advocating for France to protect world heritage sites in the Sahara, a strategy that called for continued colonial control of Algerian land and resources.

With this background, archaeology and extraction form another dichotomy close to Ourahmane’s project. While much of her past work has involved moving objects across contexts, her exhibition at SculptureCenter explores a new approach to the mediation of site through photogrammetry, a remote sensing technology that uses photographic data to accurately represent three-dimensional objects. In the film, digital animations developed from scans collected on the surface of the plateau subtly simulate passages of Ourahmane’s live footage. In other sequences, displaced fragments of landscape float in a contextless virtual space as the camera zooms and pans amid changing lighting effects. This kind of production privileges transportable information over the physical possession of an object or a place, evading certain problems of extraction while creating new and ambiguous distribution channels for forensic detail.

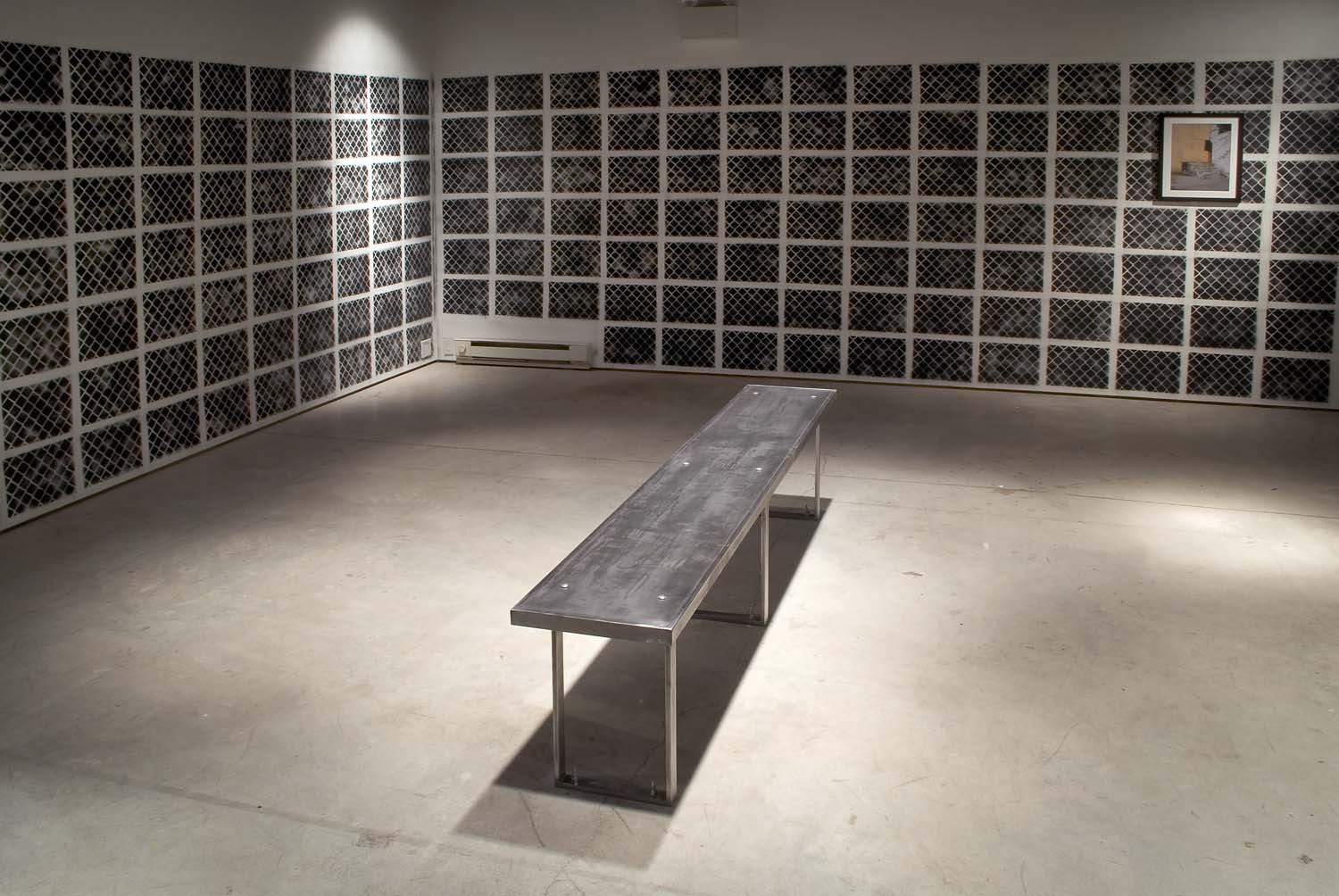

In a similar vein, a high-relief topographical sculpture produced in collaboration with Yuma Burgess replicates surface sections of the desert and was 3D-printed on site at SculptureCenter in thin tiles of black thermoplastic. The work appears as a continuous field, suspended as a monumental screen, but in actuality it is a partially invented landscape: it collapses the distance between multiple real sites, and it uses a general adversarial network (GAN) to produce new textures that fill the space between the edges of discrete scans. Like the film, the sculpture pairs excessive or indulgent visuality with speculation about what cannot be seen (for a range of reasons), but can be sensed, intuited, or imagined, a feeling heightened by the reflective luster that makes the work’s dark surface ambivalent.

In recent years, Tassili n’Ajjer has functioned as a major migration route across the African continent, engendering new narratives of violence, smuggling, and other security issues. In this context, and despite its own complexities, Ourahmane’s exhibition can be read as a rebuttal of recent characterizations, subtly animating writer Ibrahim Al-Koni’s more grave and poetic description of the desert as “the only place where we can visit death… Because it is the isthmus between total freedom and existence.” Ourahmane’s work similarly understands the desert, and perhaps the ambitions of art, as a means of seeing beyond the machinations of the present day while contending with the fact that we remain tightly bound to the political frameworks and material contingencies of the moment, the decade, the century, or somewhere beyond time.

Lydia Ourahmane (b. 1992, Saïda, Algeria) is an artist based in Algiers and Barcelona. Ourahmane’s research-driven practice spans spirituality, contemporary geopolitics, migration, and the complex histories of colonialism. She incorporates video, sound, performance, sculpture, and installation on an often large or monumental scale that has consequences beyond the walls of her exhibitions. Drawing on personal and collective narratives and experiences, Ourahmane challenges broader institutional structures such as surveillance, logistics and bureaucratic processes, and the ways these forces are registered. Her recent solo exhibitions include: Survival in the afterlife, Portikus, Frankfurt, and De Appel, Amsterdam (2021); Barzakh, Kunsthalle Basel and Triangle – Astérides, Marseille (2021); صرخة شمسية Solar Cry, CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco (2020); and The you in us, Chisenhale Gallery, London (2018), among others. Her work was included in the 34th Bienal de São Paulo (2021) and the New Museum Triennial (2018). With collaborator Alex Ayed, she presented LAWS OF CONFUSION, Renaissance Society, Chicago (2021) and was included in Risquons-Tout, WIELS Contemporary Art Center, Brussels (2020).

Video Credits

Collaborators:

Abdou Ali

AissaAbdou

Ali Aissa

Sophia Al-Maria

Berka Ayoub

Yuma Burgess

Ahmed Hamid

Djamel Hamid

Moussa Hamid

Hiba Ismail

Ismail Machar

Moussa Machar

Mohammed

Idriss Machar

Jacob Oommen

Isabel Valli

Music:

Nicolás Jaar

felicita

Yawning Portal

Sega Bodega

Editor: Robert Fox

Cinematography:

Alana Mejía González

Jacob Oommen

Animation: Yuma Burgess

Sound Mastering: Joe Ware

Color: Nadia Khairat

Research Assistant: Sarah Ourahmane

Production Manager:

Khaled Bouzidi

Yanis Ouabadi

Graphic Design: Collin Fletcher

Special thanks to the Algerian Ministry of Culture and Arts and the Tassilin’Ajjer National Park.

The exhibition is curated by Kyle Dancewicz, Deputy Director.

Lydia Ourahmane’s new moving image work Tassili, 2022, is commissioned and produced by SculptureCenter, New York; rhizome, Algiers; Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris; Kamel Lazaar Foundation, Tunis; Mercer Union, Toronto; and Nottingham Contemporary.

Lydia Ourahmane: Tassili is organized in partnership with B7L9 Art Station, Tunis, where it will travel in 2023. Presentations of Ourahmane’s video work are planned for 2022-23 in partnership with the Open Space program of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (Oct 7, 2022–Feb 27, 2023); Mercer Union, Toronto (2023); and rhizome, Algiers (2023). Tassili was also included in Hollow Earth: Art, Caves & The Subterranean Imaginary at Nottingham Contemporary (Sep 24, 2022–Jan 22, 2023).