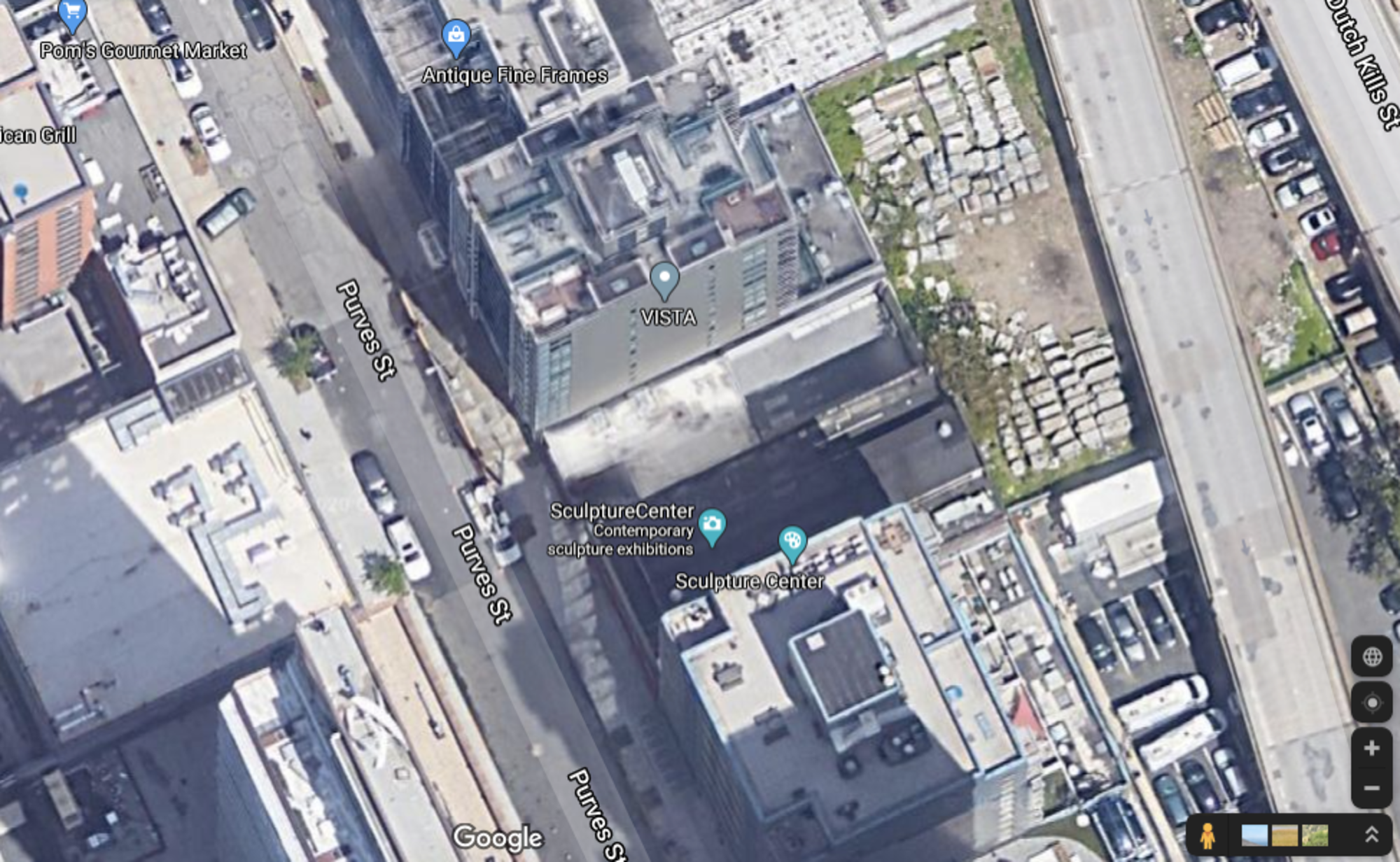

During the exhibition the gallery is closed, no.1 Exhausted in Place

Via Google Satellite

Editorial

Bare Time

For the first time in contemporary history, everyone – or almost everyone – on the planet is faced with the conditions of being an artist. That is, waking up in the morning and having to invent our lives and make them livable. Or, to put it in other words, we are faced with the daily challenge of making our lives into works of art. Each day we are faced with the questions: how have I been living and how can I live differently, make changes, incrementally, consistently? The hyper-accelerated conditions of life that we were used to, the incessant pressure to perform, produce, post, repost, like, had filled life with content and were abruptly paused to a standstill. Suddenly we are faced with empty time, unscheduled time, deregulated time, time out of content, time without labor, bare time.

Of course, this is a romantic conception of an artist or an artist’s life (as Amy said, an artist’s life might have looked like the quarantine, but life is not always a f**king disaster—at least not for the most part, or for everybody at all times). But we are, for better or for worse, faced with this bare time instead of time scheduled, calendared time. Romantic or not, now we are faced with the imperative to create a livable life, maintain a life and try to make it less dull and wasted, or more fulfilling. Art makes something out of nothing, and we have a lot of the latter at our disposal at the moment. Artists, first and foremost, are people who own their time and claim it for their own, fill it up or empty it out. As pleasurable as it sounds, this is not an easy feat. No one asked them to do it or is going to fill their time for them, no one expects them to succeed or mourns their failure, and yet day after day, they would wake up and propel themselves to engage with an irrational yet logical activity of making and unmaking art.

Klein created The Void (1958), Arman The Full Up (1960); Lozano “dropped out” and Sturtevant “re”-made, and these two approaches could at least metaphorically be instrumentalized to think about what to do with the day and the night. With risk of hyperbolic exaggeration, there are two kinds of artistic approaches in making work. Those who take content out until they are faced with the least possible amount of it, no longer possible to get rid of, and those who accumulate content over content until they reach a point of saturation before everything starts spilling over and out. This is not a matter of minimal and maximal. One can be a reductive maximalist and an aggrandizing minimalist. We are faced with the question of how to fill our days, or how to empty them out.

Like it or not, right now, in a moment of global catastrophe, with death looming behind every touch, everybody (as it has been proclaimed before for other or similar reasons) is an artist—“and everyone hates it.” Artists are best equipped to deal with solitude, a sequestered life, unscheduled time. But this is art without contemporary art, there is no institutional mandate that propels the quotidian, no critical validation of the everyday, there are no deadlines in place to dust off the trivial. There is no contemporary art in quarantine yet there are decisions to be made towards an aesthetics of a tolerable life and to make it better, different, and less intolerable.

We are faced with the question, what kind of life is worth living? (Foucault) We are tasked with the dilemma of how to live a beautiful life. To make a life out of nothing. Out of incompetent governance, dreadful ambivalence, sluggish hourglass, banality of groceries, lethargic anxiety of the threat of furloughs and declined sustenance, out of the fear of not making rent and why to pay it. We are all pondering about the reason and value of what we have been doing, and why have we been doing it the way we did, can we do it differently, can we do it better, should we give it up altogether, jump ship, do something else? Is it satisfying, is it draining, does it give us joy, are we just wasting our lives away doing something we don’t want to do? These are all aesthetic questions. These are all questions that artists face when they get to their studio, or post-studio, when they stare at a blank page or canvas, or open whatever application they design their work in. These questions are fundamental, or existential questions, but we usually don’t bother asking them, because we have to be at the office or at the bar, on the train or the canteen, in a meeting room here or elsewhere.

There are people who are out there making our sequestered living possible by sacrificing theirs. We are nevertheless left with a romantic proposition, perhaps even an obsolete romanticism that could propel a semblance of meaning in the face of a significant loss of human life. What we can or cannot do is a question that we cannot turn away from as we pace around a shrinking life in a shrinking city, in a vanishing neighborhood and a room that is filled with our being and we cannot quite fill it up.

- Sohrab Mohebbi

Over the next few weeks while we are sequestered in our homes and SculptureCenter’s exhibitions remain closed, we will try to bring instances of artists’ making and unmaking of art, and the emptying out and filling up of our lives lived on and offline. The title of this series is borrowed from a string of exhibitions mounted by Robert Barry in Amsterdam, Turin, and Los Angeles in 1969-70. This first issue is structured around Rafael Domenech’s exhibition Model to exhaust this place (SculptureCenter Pavilion).

Exhausted in Place

While the main highroads of planetary commerce are at a standstill or slowed down to an unprecedented scale, their efficacy is under scrutiny and their vulnerabilities are exposed. The urban centers are practically empty and resemble Hollywood fabrications, institutions (governmental or otherwise) are closed or operating on extremely reduced scales.

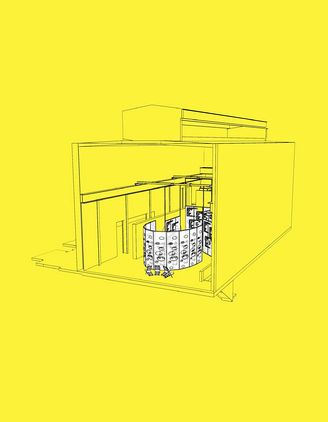

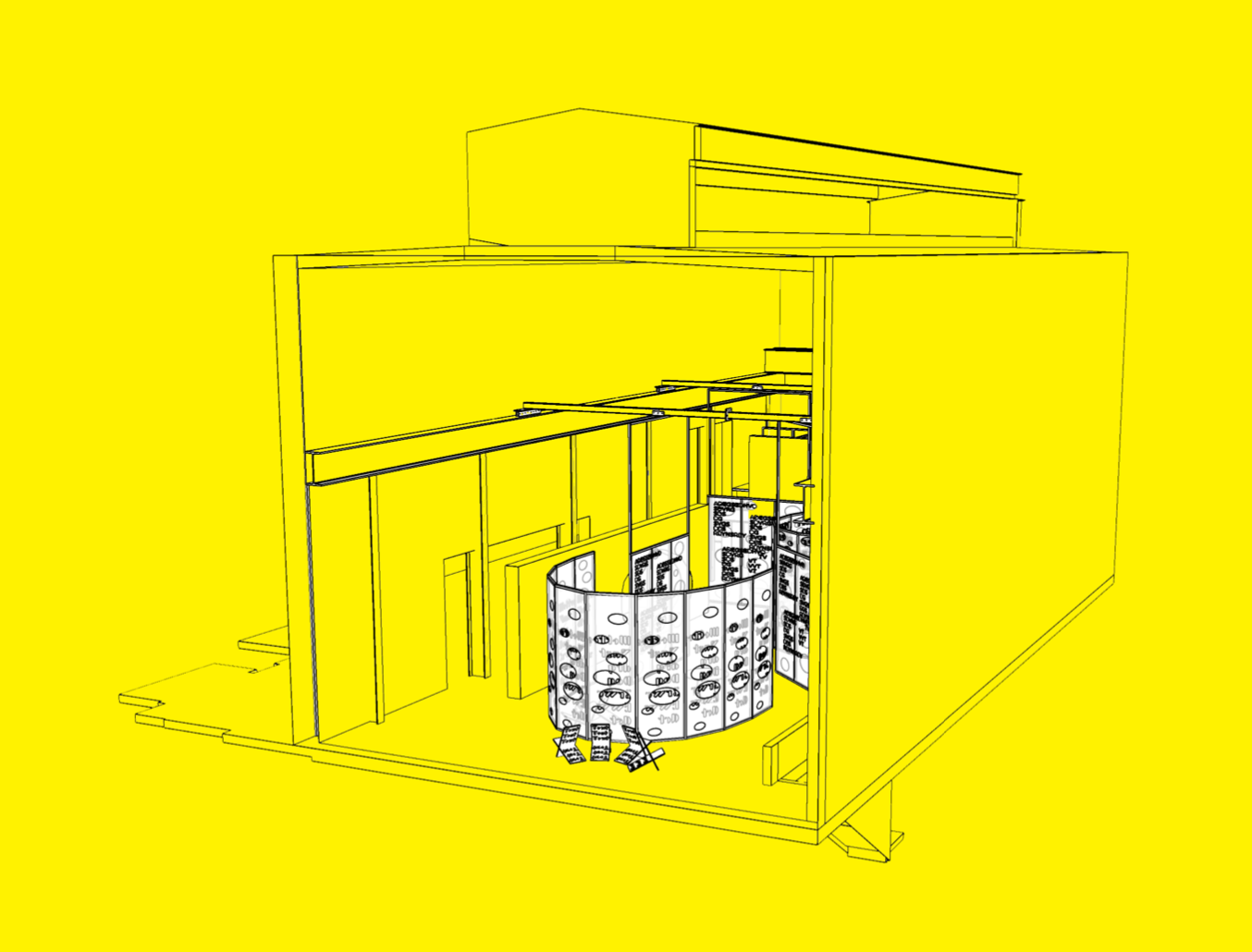

Like most other institutions, SculptureCenter is closed, yet the building still holds an exhibition by artist Rafael Domenech. In his work, Domenech considers how artwork exists in the ecology of a practice at the intersection of studio, institution, and urban space, while addressing an economy of means in his production. The artist ponders how material histories and applications are developed following standardized metrics of life and how artworks operate within this infrastructure, or “invisible architecture,” as Domenech refers to it.

New Artist Publication

Domenech’s publication, produced in conjunction with his exhibition and now available as a PDF below, looks at how semantic and physical architectures create contemporary art’s institutional context. Its primary essay, Work of art in the age of codes and regulations, is an attempt to capture some of the main concerns and suggestions of the artist’s work. Perhaps some of these ideas become more evident in a moment when the structures that contemporary artworks engage with are functioning at much lower capacities.

Rafael Domenech: Model to exhaust this place (SculptureCenter Pavilion)

SculptureCenter and Isométrico Publications, 2020

In light of recent public health guidelines, follow Rafael Domenech's instructions for turning a t-shirt into a mask.

Related Materials: DeLanda, Friedman, Venturi, Scott Brown

The selection of videos below related to various aspects of Domenech’s interests and practice, in particular questions around material histories, improvised architecture and the significance of signs and symbols in architectural practice.

Manuel DeLanda discusses his book A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History (1997), where he outlines his material history of urbanization and the notion of cities as accelerators of historical time. The book analyzes the history of cities from three angles: their relationship to sources of energy; their metabolism, and their relationship to plants and other organisms; and, finally, the linguistics of cities as propellers of particular dialects and centralizing forces of language. Of particular interest to the current moment is DeLanda’s analysis of the ecological crisis in early 14th century in Europe, just prior to the spread of the plague.

Visionary architect Yona Friedman discusses his theory of popular architecture. He prioritizes the user over the architect with emphasis on the development of simple, adaptable technologies and materials over deterministic design.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown talk about their architecture practice and ideas discussed in their seminal book Learning from Las Vegas (1972), in particular the notion of symbolism in architecture.

Links: From the archives, from the web

“Social Contagion: Microbiological Class War in China” from 闯 Chuǎng expands on the relationship between capitalism and increased urbanization and how cities become “epidemiological laboratories,” to quote DeLanda, following the environmental crisis of capitalist overdevelopment. 闯 Chuǎng is a journal and blog dedicated to analyzing the ongoing development of capitalism in China, its historical roots, and the revolts of those crushed beneath it.

Banu Cennetoğlu in conversation with Kaelen Wilson-Goldie. Cennetoğlu’s practice calls out the incapacity of the conforming systems of regulation, categorization, classification, and normalization to capture and contain the human condition. In conjunction with her 2019 exhibition at SculptureCenter, the artist was joined in conversation by writer and critic Kaelen Wilson-Goldie to discuss the major concerns of her wide-ranging, cross-disciplinary practice.

“A little exercise to make sure that, after the virus crisis, things don’t start again as they were before,” from Bruno Latour’s blog. In the face of the forced suspension of most activities, philosopher Bruno Latour poses six questions to take stock of those we would like to see discontinued and those, on the contrary, that we would like to see developed.

Tune In

A Journey Around My Room (Christian Nyampeta on Instagram)

Piscesbabe123 (dies smely)

C. Spencer Yeh: Solo Violin West Coast USA 2017

Goth Talk (Live from the Cave)

Club Quarantine (See you there…)

Postscript

Email response from Rindon Johnson re: Bare Time

Resources

Crip Fund

Housing Justice for All

Mask Crusaders

Creative Capital

SculptureCenter is available to assist in navigating these resources. For assistance, please email info@sculpture-center.org.