In Practice: Literally means collapse

In Practice: Literally means collapseMay 12 - Aug 1, 2022

- Images

- Text

- Events

- Materials

- Press

- Sponsors

- Related

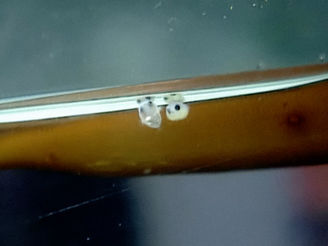

Allen Hung-Lun Chen, Offering IV (an eave for SculptureCenter), 2022. Black walnut, cast aluminum, leather, ratchet-straps. 60 × 72 × 36 inches (152 × 184 × 91 cm). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Charles Benton

In Practice: Literally means collapse is an exhibition of new works and artistic meditations that consider the notion of the ruin expanded to include social traditions as well as physical infrastructure. From built environments and structures of circulation to protocols and belief systems that shape social and political subjects, infrastructures are in constant generative friction with decay. Rituals of maintenance are designed and performed to prevent what is constructed from being physically, or subjectively, ruined.

Diagnosing a contemporary obsession with ruins, artist and theorist Svetlana Boym has written, “‘Ruin’ literally means ‘collapse’—but actually, ruins are more about remainders and reminders.”[1] Boym elaborates that as sites, ruins can simultaneously trigger both potential nostalgias and imagined futures. Existing among ruins is existing among spaces of asynchrony—of histories and timescales collapsed.

The artists in the exhibition trace collapse through material and metaphor. Some examine the failures of cities and other containers of information, working with and against the anxieties of deterioration. Others remind us of the strategic disintegration and flattening of symbols and aesthetics. And some embrace the breaking down of space, time, language, and other familiar logics. In Practice: Literally means collapse collects these overlapping studies in the paradoxical timescale of ruin.

In Practice: Literally means collapse features newly commissioned sculptures, installations, and video works by eleven artists: Marco Barrera, Allen Hung-Lun Chen, Violet Dennison, Enrique Garcia, Ignacio Gatica, Cherisse Gray, Jessica Kaire, Fred Schmidt Arenales, Alan Martín Segal, Stella Zhong, and Monsieur Zohore. The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully-illustrated catalog and a season of programming. In Practice: Literally means collapse is organized by 2022 In Practice Curatorial Fellow Camila Palomino.

Allen Hung-Lun Chen has hand-carved an architectural detail from a Taiwanese temple for this meditation on the rituals of maintaining structures and tradition. The swallowtail-shaped roof ornament, referring to eaves found on temples in Taiwan and throughout East Asia, is made of black walnut, a wood indigenous to the United States, where Chen is currently based. The eave sits on an aluminum-cast replica of a folding table, a support commonly used in East Asia to make offerings, such as fruits and flowers, to spirits throughout the day. Through this offering of the eave, Chen gives some permanence to a traditionally transient quotidian practice. Situated on the ground floor, the installation is intended to provide a protective force within the confines of SculptureCenter.

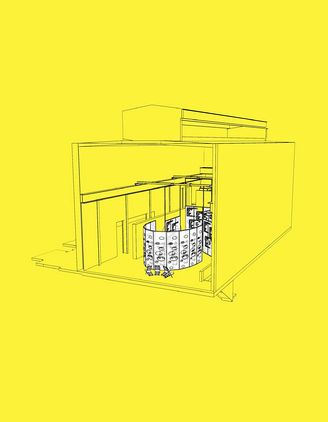

Monsieur Zohore’s immersive installation draws parallels between Catholic traditions and the contemporary ethos of late capitalism. Zohore is inspired by an ancient and extant ceremony performed yearly at the Pantheon in Rome in celebration of the Pentecost: roses are released from the building’s oculus to symbolize the descent of the Holy Spirit. Zohore translocates this sensorial pageant to the venue of a manufactured money-blowing machine—a fated encounter between two public spectacles. The machine sits within its own excess, littered with a skirt of rose petals and cash. When it is entered and activated, a swirl of money and petals is accompanied by Zohore’s voice seductively reciting Baptismal promises against a catchy string of sound. The track played within the machine is a hauntingly playful electronic interpretation of the twelfth-century chant “Veni Creator Spiritus,” set to a musical score by composer Joshua Coyne. Embracing “the glamor of evil,” MZ.21 (Pentecost) embodies the gamification of liturgy, exploring the institutional control that is conditioned by rituals of worship, as well as the entwined relationship between the machinations of Catholicism and capitalism.

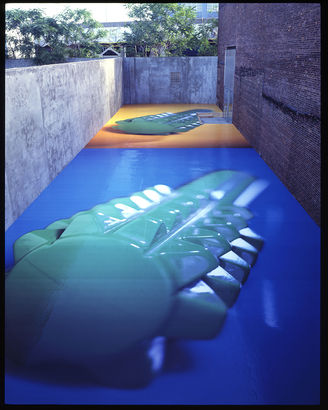

Marco Barrera uses waterways as a subjective cursor with which to trace the industrialization and development of New York City. Along a narrow hallway is a selection of heavy metal doors that once secured safes within small businesses, warehouses, and homes in the Northeastern United States. Produced in the Rust Belt at the turn of the twentieth century, their interior surfaces are decorated with paintings of flowing waters by anonymous artists. Meandering streams and picturesque sailboats accompanied reserves of cash that had been sequestered from circulation.

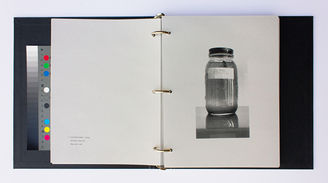

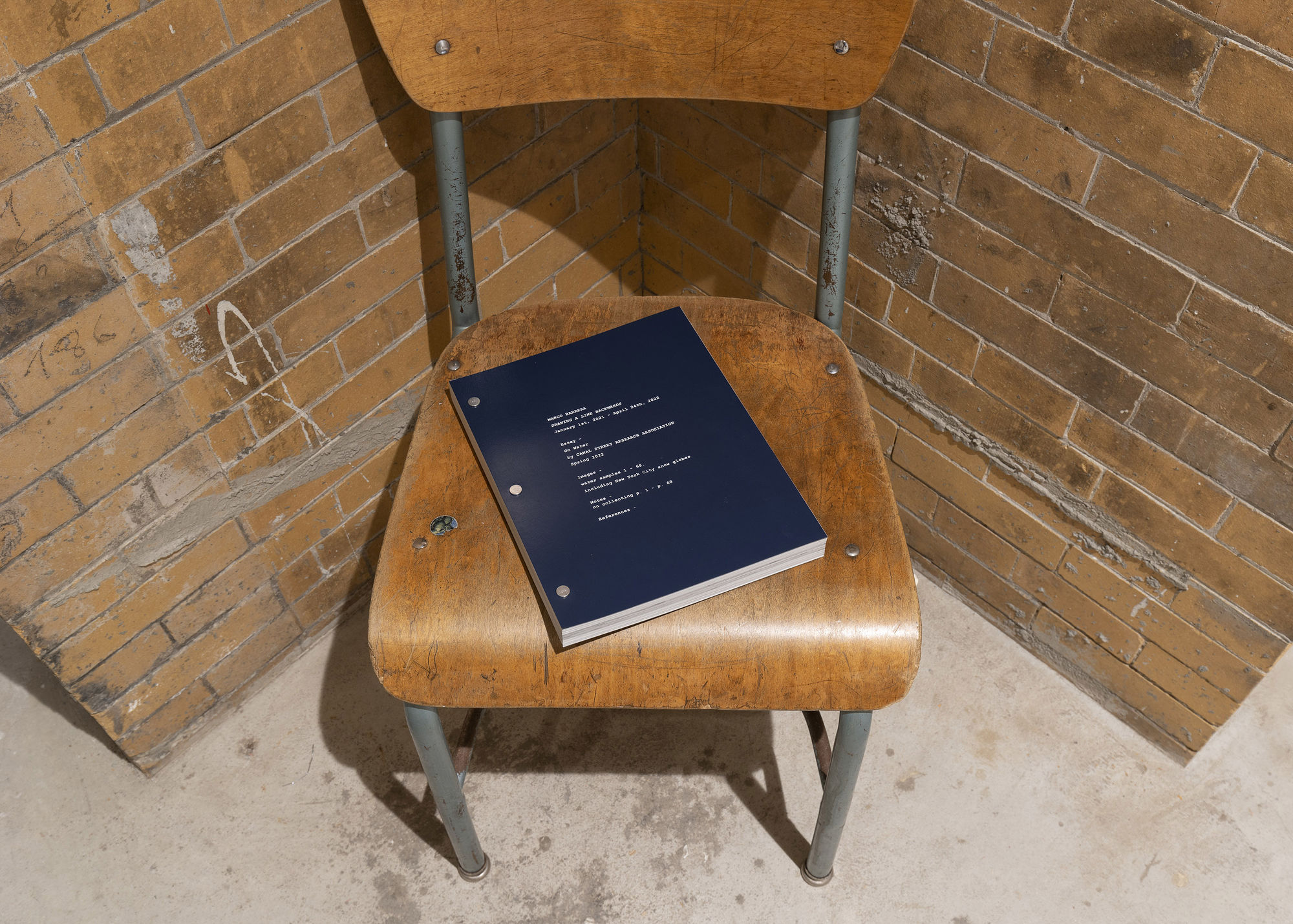

At the end of the hallway, Barrera has installed a collection of bottled water samples on a steel shelf that visitors can sort through. The source of each sample is related to a different aspect in the development of New York City, from a faucet at Empire City Casino in Yonkers to runoff from a quarry in Vermont that provides marble used for the ornamentation of municipal buildings in Lower Manhattan. An accompanying book made by the artist indexes the samples and sites with diaristic and historical notes. The publication includes an essay by the Canal Street Research Association that traces the distribution of wealth in New York City through the seemingly infinite circulation paths of currency and plumbing. Taken together, Barrera’s two installations shape a dislocated cartography of the urbanization of the city.

Violet Dennison uses a knot system to encode poems and writing in colorful large-scale installations she weaves from pneumatic tubing. Like a sigil, each knot in the black tubing holds an embedded message and prayer. The interlacing of the twists is guided by a computer program, developed by Dennison and an engineer, that encrypts text by translating it into a binary language that instructs on whether to pass a tube over or under. Produced through a series of repeated actions, the knots’ unique shapes hold information. Another layer of repetition creates patterns with these knots, further distancing access to the coded information. The title, Maniac Double, is a reference to DanceDanceRevolution, a music video game that similarly directs action through visual code. Dennison is interested in the optimization of communication between individuals and technologies, but also in the exhaustion of legibility and symbolic power through flattened and ornamental forms.

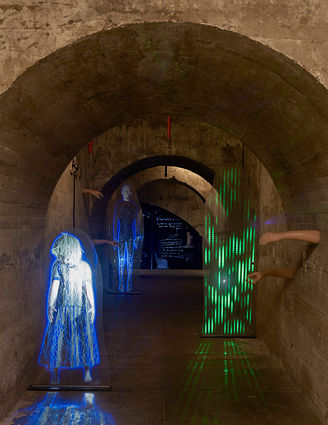

Stella Zhong’s three site-specific structures at the entry to SculptureCenter’s arched corridor contain speculative landscapes informed by playful interpretations of scale. Tucked under and over the smooth planes of each maquette are populations of diversely shaped miniature units that sprawl into unseen corners. Similar to game pieces, they are engineered to perform precise and unexpected roles. Glimpses of these objects and their activities surface throughout the installation. A single filament stretches diagonally, connecting two of the structures. Under the reflective plane of a third, entities in the familiar forms of pebbles and chips unite in mitochondrial patterns, building a tight system of entropy through tensile conduits. The units and the structures that contain them suggest a planetary organization, yet they resist conventions of gravity or time, existing as dimensions untethered from conventional logic.

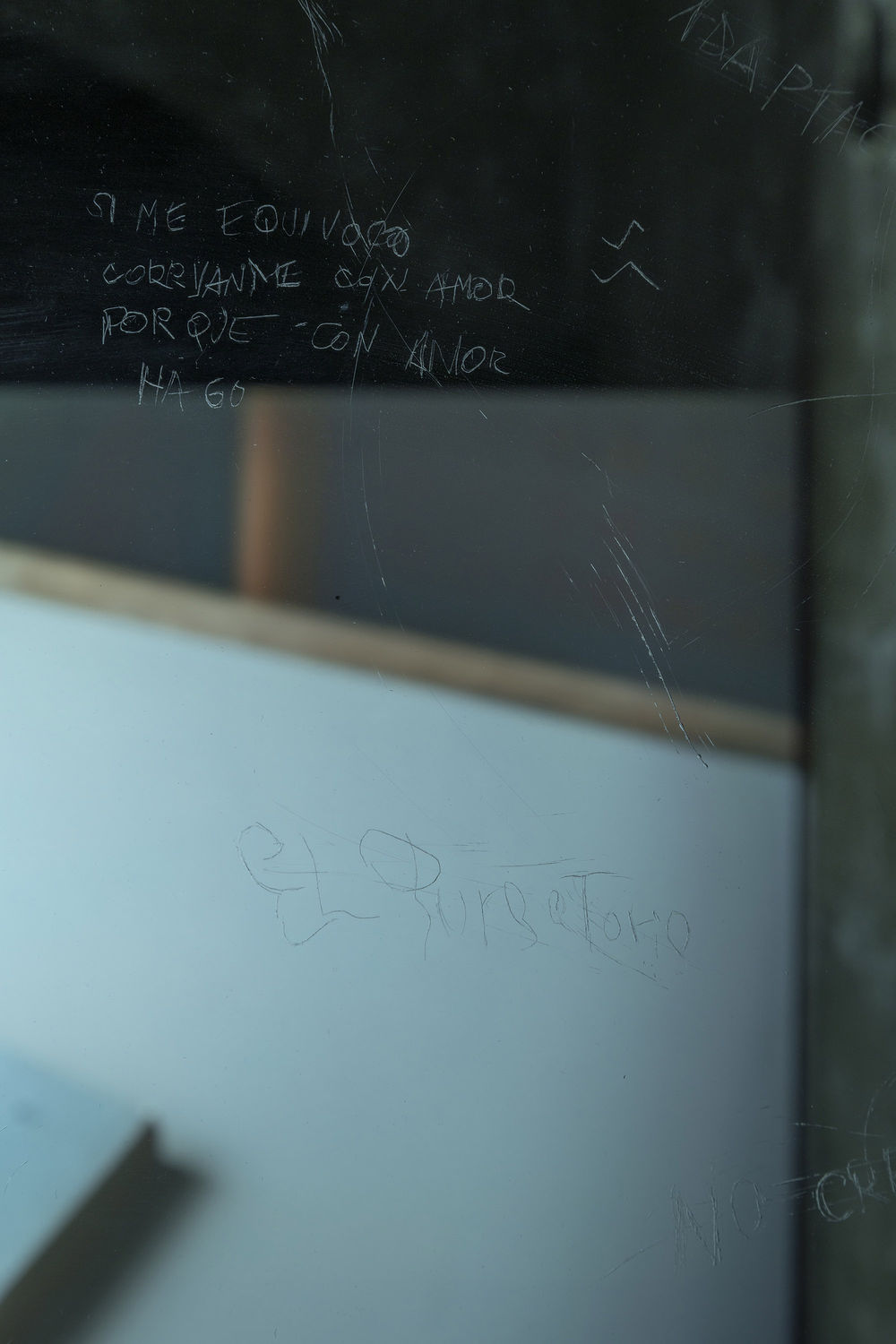

Alan Martín Segal’s video and audio installation Incomplete Disappearances meditates on the physical and social infrastructures of Buenos Aires. The work draws on a series of texts, including the artist’s personal correspondence as well as a short story by Ezequiel Martínez Estrada titled “La cabeza de Goliat,” a microscopic analysis of social norms and practices in the Argentinian capital. Segal combines nondescript shots of the city with repetitive reenactments of mundane gestures that begin to verge on the uncanny. This accumulation of small gestures and interactions is viewed through a suspended sheet of glass that imposes an oblique distance from which to contemplate the haunting presence of colonial fantasies and ideologies embedded in urban routine.

Jessica Kairé’s Folding monument (Christopher Columbus Statue, Columbus Triangle, Queens, New York) emerges from an ongoing practice in which she translates historic monuments into soft sculptures mobilized by viewers to become allegories for the construction of history in public space. In previous related works, Kairé created fabric replicas of monuments that commemorate contentious moments and political figures in Guatemala. For this iteration, she interprets the vandalized pedestal that supports a statue of Christopher Columbus in Astoria, Queens—one of the five Columbus statues distributed among New York’s boroughs. Installed in a collapsed state, the sculpture is revived by being pulled up by attached ties, which visitors are invited to do collaboratively. In inviting this collective act, Kairé gestures to the participation required to challenge shared histories.

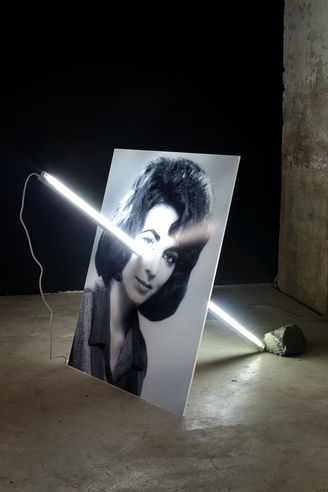

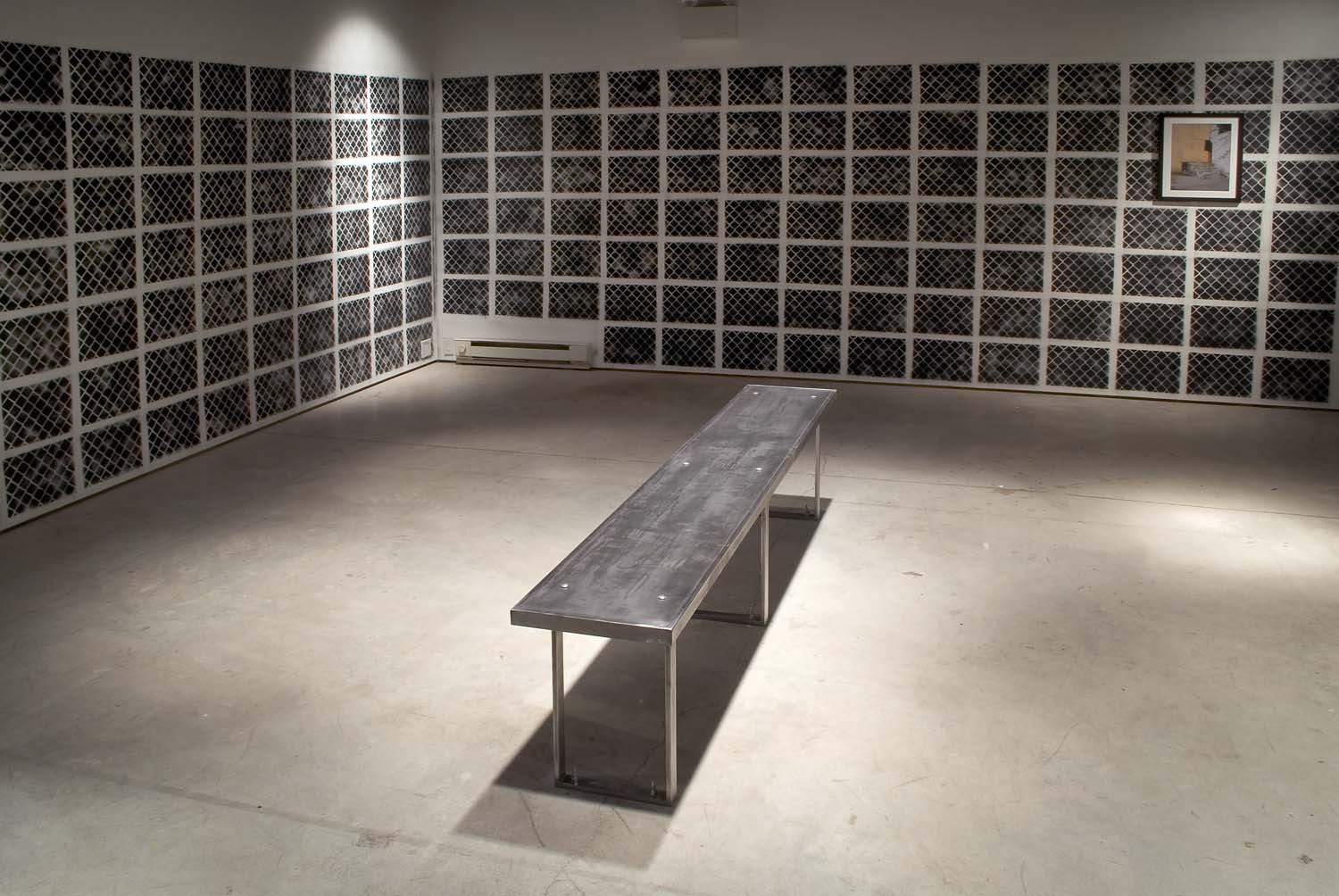

Enrique Garcia uses photography and bricolage to examine public plazas in Mexico, making visible the legacies of colonial design while collecting moments of daily movement and deterioration. In this series, Garcia mounts images he has made at select locations: La Antigua in Veracruz, an early failed Spanish settlement where a house allegedly belonging to Hernán Cortés still stands, overgrown with roots and vines; Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, where a sixteenth-century Catholic bishop designed the plaza and new master plan for the city; and the Zócalo in Mexico City, where the Spanish built over a ceremonial space of the Aztec. Each location is documented at a macro level through photography as a conduit to urban life, and on a pedestrian level through the incorporation of residual objects found in situ. The ambiguous objects, from earrings to rusted pipes and other worn metals, bear the traces of unknown individuals and routines. In each framed work, Garcia reveals the asynchronous layers of history in public spaces.

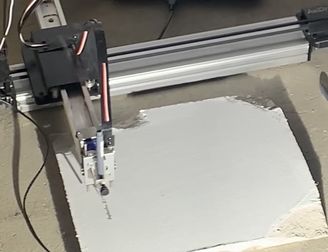

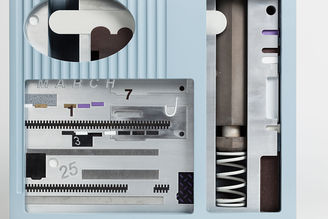

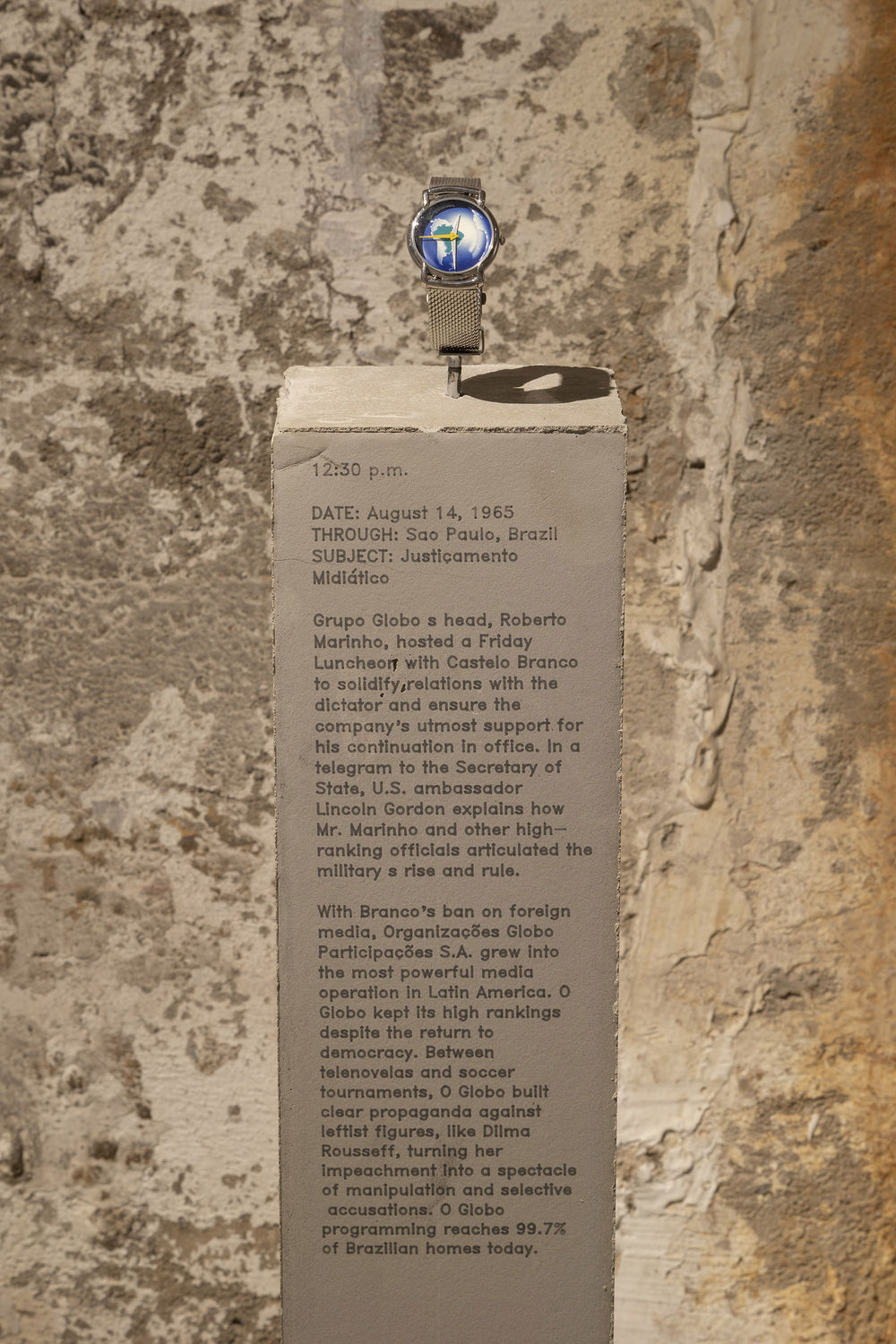

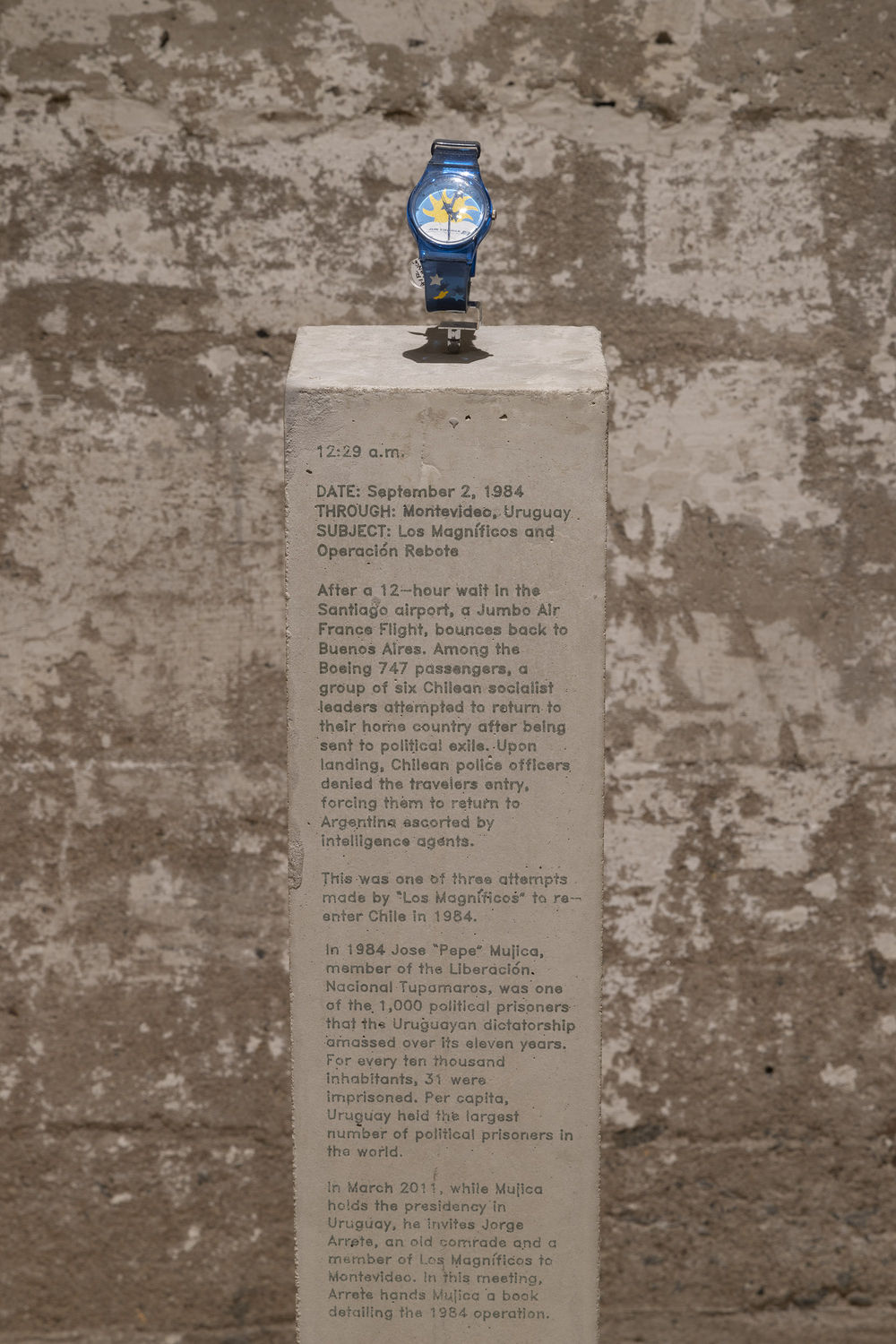

Ignacio Gatica uses a collection of political souvenir wristwatches to narrate the legacy of US intervention and neoliberalism in Latin America. In 2019, the United States sent Argentina a batch of CIA files in what was at the time the largest government-to-government transfer of declassified documentation. Excerpts from the archives, elaborated by Gatica’s research and writing, were printed on concrete plinths with a mechanical handwriting machine. Resting on top, at wrist level, are watches Gatica acquired from various states and organizations throughout the Americas. Each ticking timepiece has been modified by the artist to endlessly mark the moment of an event chronicled in the CIA documents. On the wall is a poem borrowed from the Chilean poet Carlos Soto Román that is loosely based on the biography of a particular CIA agent. The total accumulation of towered watches and texts represent a network of overlapping political and social histories and suggest the monolithic, mechanistic nature of the US’s global interventions.

Cherisse Gray has assembled a site-responsive installation that reroutes conventions of architecture and ornament. Distilling symbols of bureaucratic tradition, she reconfigures them to implicitly contrast hostile and accommodating design. The built environment Gray has constructed implies the absence of its inhabitants. A miniature spiral steel staircase leads into a structure made of drop ceiling tile, within which red lights glow and an oscillating fan ruffles a poinsettia—traces of cheap, standardized building materials are refashioned into a droning home for a mouse. Near this element is the full-scale imitation of a bench from a brutalist building in the Philippines commissioned by the Marcos regime. The artist has transformed this awkward and antisocial piece of furniture into a heated seat for visitors to enjoy. On the floor, a carpeted red stage supports an organically shaped lamp sculpted by the artist. The final element is a ceiling fixture that casts diffused light from above to join the independent elements into one spatialized encounter. The myth of universal utility in objects and systems breaks down in Gray’s installation.

Fred Schmidt-Arenales’s latest film, Committee of Six, is premised on the reenactment of a series of closed-door meetings between university officials and community organizers in 1955 at the University of Chicago. Archived minutes of the meetings reveal plans and strategies for displacing Black communities and limiting racial integration. Departing from the historical minutes as a script, the film follows the group of six performers as they play the historical participants. The actors' interpretations of the original exchanges are interlaced with their off-script and off-set reflections on present-day policies and ideologies. Overlaps and continuities between past and present emerge through the relational dynamics between actors serving as a proxy for those of the original meeting members. Through the complex activation of historical evidence, the film points to the cyclical nature and consequence of discriminatory urban renewal.

[1] Svetlana Boym, “Ruinophilia,” in The Off-Modern (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017).

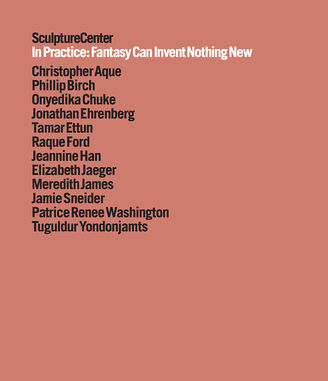

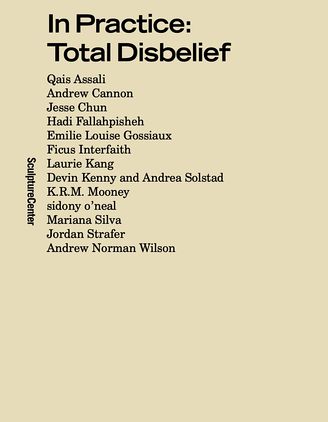

In Practice

SculptureCenter’s In Practice open call program supports emerging artists and curators in creating new work for exhibition at SculptureCenter. Since 2003, In Practice has provided more than 230 artists with the essential resources of space, funding, time, curatorial support, and administrative guidance to help turn their ideas into reality. Exemplifying the spirit of SculptureCenter’s mission, In Practice supports innovative artwork, fosters experimentation, and introduces audiences to underrecognized practice and new ideas. The program offers participants the opportunity to develop and present work in what is often their first institutional exhibition in New York City. To learn more about the program, visit www.sculpture-center.org/in_practice.

Events

Sponsors

Major support for the In Practice program is provided by the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. In Practice is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Leadership support of SculptureCenter’s exhibitions and programs is provided by Carol Bove, Lee Elliott and Robert K. Elliott, Jill and Peter Kraus, Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation, Barbara and Andrew Gundlach, Jacques Louis Vidal, Miyoung Lee and Neil Simpkins, Eleanor Heyman Propp, Libby and Adrian Ellis, Benoit Bosc and Torsten Schlauersbach, Jamie Singer Soros and Robert Soros, Candy and Michael Barasch, Sanford Biggers, Jane Hait and Justin Beal, and Amy and Sean Lyons.