In Practice Winter '05

In Practice Winter '05Jan 16–Apr 10, 2005

- Images

- Text

- Events

- Sponsors

- Related

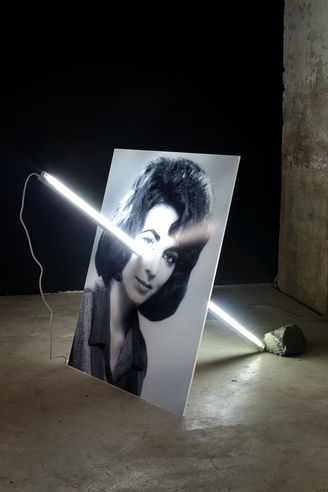

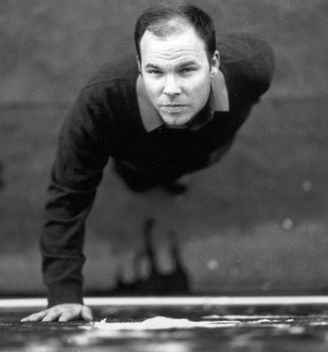

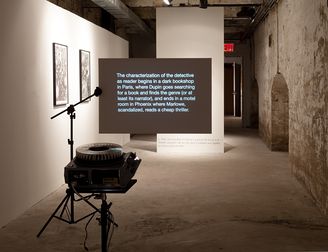

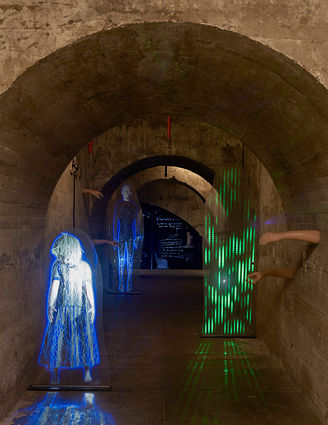

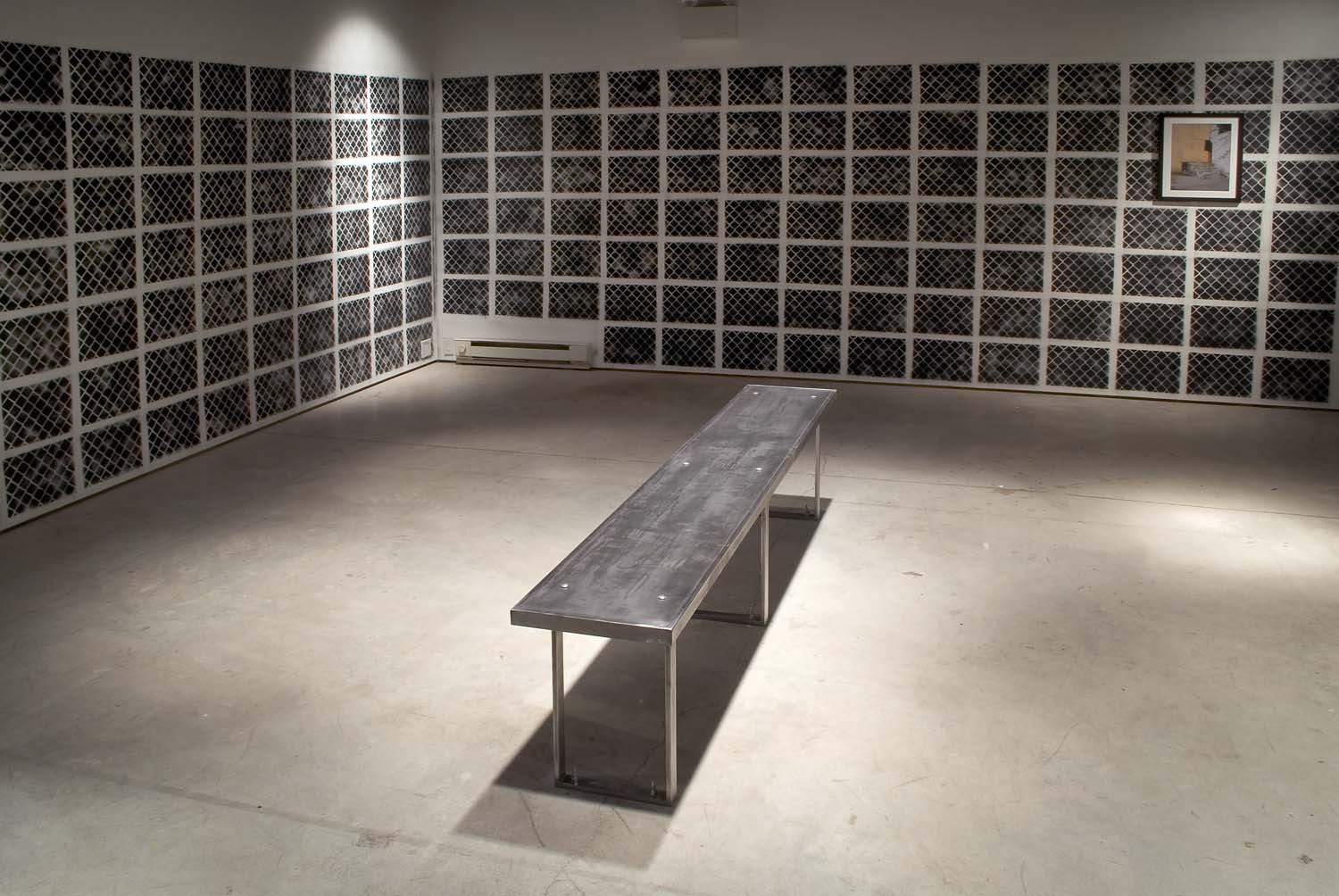

Installation view, In Practice, SculptureCenter, 2005.

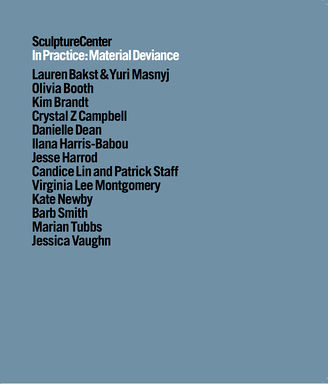

The works in this exhibition are commissioned through SculptureCenter's In Practice project series, which supports the creation and presentation of innovative work by emerging artists. The projects are selected individually and reflect the diversity of approaches to contemporary sculpture.

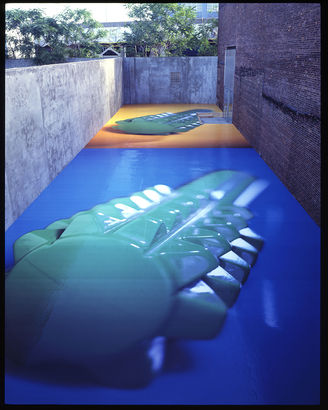

Max Goldfarb's site-specific installation Crenellated Boundary Wall (2004) creates a porous barrier out of the invisible -- and highly regulated -- frequencies of the radio spectrum. The artist installs forty-six forms along the top of the sculpture yard's 130-foot-long cinderblock wall, turning it into a medieval crenellated fortress. Each shape is painted in stripes and blocks of bright colors, corresponding to the various categories of U.S. radio frequency allocations: public safety, government, broadcast, cellular, marine, etc. Installed atop the fifteen-foot-tall wall, the crenellations combine obsolete defensive architecture, abstract color fields, and the politics of public electromagnetic real estate, to frame a contained and controlled space infiltrated by people and information.

Nicholas Herman, also on view in the sculpture yard, presents two new works. Continuing his ongoing interest in masquerade and the role of civic monuments to mark space, the artist transforms piles of castaway concrete into totemic, anthropomorphized forms. Entering the courtyard, viewers are faced with the sculptural gravity of blackened concrete fragments. On closer inspection, one pile reveals a grinning bronze wolf mask, while the other is festooned with some of the trappings of a traditional civic memorial. In addition, each form is covered with subtle traces of gold-leaf. As if possessed by an epic narrative, the large blocks of urban detritus become folkloric landscapes.

Elana Herzog uses fabric as a parasite in space. Her pieces of cloth -- parts of drapes, bedspreads, towels -- are caught between a moment of growth and one of decay: simultaneously decorative pattern and decomposed rejects, luxury and nostalgia. The artist builds a series of three walls, forming a slaloming pathway through SculptureCenter's lower-level galleries. Attached to the walls by thousands of staples are not textiles, but traces of textiles: fragments of shredded yellow cloth residues. The leftovers of a violent process of tearing materials apart, these abstract "paintings" are striking in their formal composition and optical effects. In this new piece, Herzog has extended her study of surface and has incorporated SculptureCenter's own walls. Bleeding from the artist's built sheetrock to the building's rough and eccentric masonry walls, her torn textile shapes accumulate layers: already an archeology of material and process, the work merges with place and jumps between old and new, remembered and invented.

Linda Post presents her new work An Object That Can Be Moved, an experiment linking sculpture to video, space, and choreographed dance. In SculptureCenter's lower-level galleries, the piece includes four videos projected in an installation of common objects including cardboard boxes, a step-ladder, a work-light, and a television, most of which also (re)appear in the video footage itself. The videos, Box Perspective, Box Push, Box/Dark, and Ladder/Kneel portray a group of actors repeatedly performing a series of choreographed movements in an empty warehouse: anonymous characters from a story-less play push boxes across a room, snap photos of each other from a ladder, and cross through an empty space in carefully planned -- if mundane -- motions and gestures. Walking through the artist's installation, viewers physically penetrate the stage-set the videos and actors have created, and consider their own trajectory through space.

Justin Lowe's site-specific installation dramatically transforms a seventy-foot long gallery in SculptureCenter's lower-level and asks viewers to walk through, crawl under, and step over a furniture-fort made of scavenged sofas, chairs, bed-frames, refrigerators, carpeting, and many other objects and materials reflecting domestic space. After passing through dense tunnel-like sections of furniture, viewers emerge into a series of clearings that become quiet hide outs: cabinet-of-curiosity moments within an engulfing junkyard of household objects. Making their way through the artist's installation, passersby appear and disappear, as if swallowed by an overcrowded and cluttered house.

Karlis Rekevics's new piece at SculptureCenter investigates the psychological impact of familiar and often over-looked urban structures: barricades, highway overpasses, signage, billboards, lampposts, traffic lights, and rooftops. Captured sculpturally in a lower-level gallery, the work becomes a crossroad: heavy abstract shapes are stacked and arranged throughout the space, creating disorienting but graceful juxtapositions of places, imageries, and vantage-points that evoke specific experiences, but leave room for personal associations. Made with unpainted plaster and lights, Rekevics's installation combines the permanence of construction materials with the impermanence of construction sites: his spaces remain fictions, physically imposing yet perceptually elastic.

Michael J. Schumacher uses sound to articulate a trajectory through one of SculptureCenter's seventy-foot long lower-level galleries. Playing across a collection of over twenty speakers -- including vintage models from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s -- the artist's sound work is generative in structure: without beginning or end and produced in real-time, the computer-driven composition creates both a unified sonic fabric for the whole space, as well as more intimate moments of sound fragments, encountered as viewers make their way through the gallery. Schumacher uses a variety of sources, including analog synthesizers, improvising musicians, digital processes, and field recordings, each sound chosen to correspond to the tonal characteristics of the individual speakers. The installation's effect is one of displacement: no matter where the listener stands, a significant sonic form is taking shape somewhere else and therefore leads them to repeatedly walk back and forth through the space, rupturing the usual motions the architecture encourages.

Sponsors

SculptureCenter's exhibitions and public programs are supported by The Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts and The Lily Auchincloss Foundation.