Niloufar Emamifar, SoiL Thornton, and an Oral History of Knobkerry

Niloufar Emamifar, SoiL Thornton, and an Oral History of KnobkerryOct 14–Dec 13, 2021

- Images

- Text

- Events

- Materials

- Press

- Sponsors

- Related

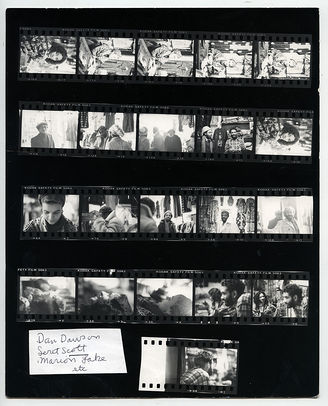

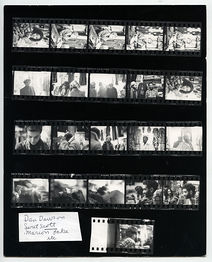

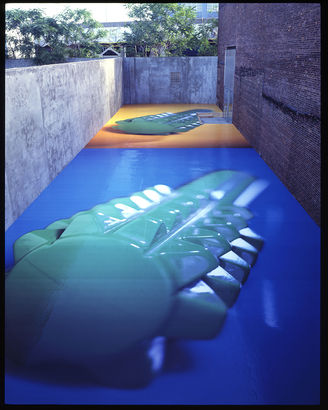

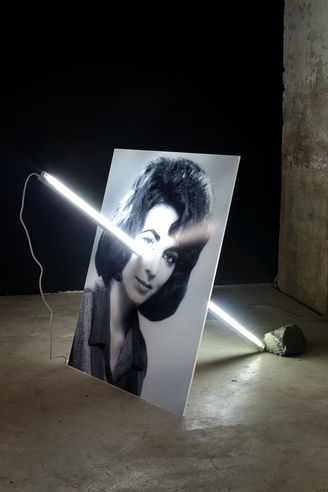

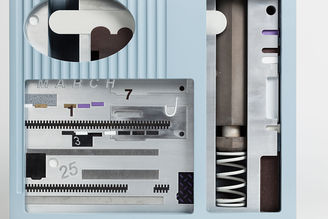

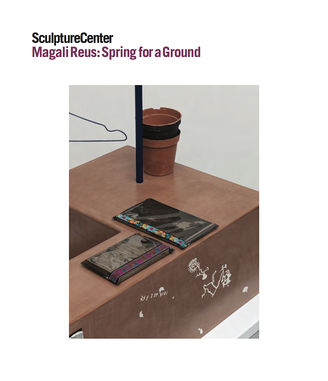

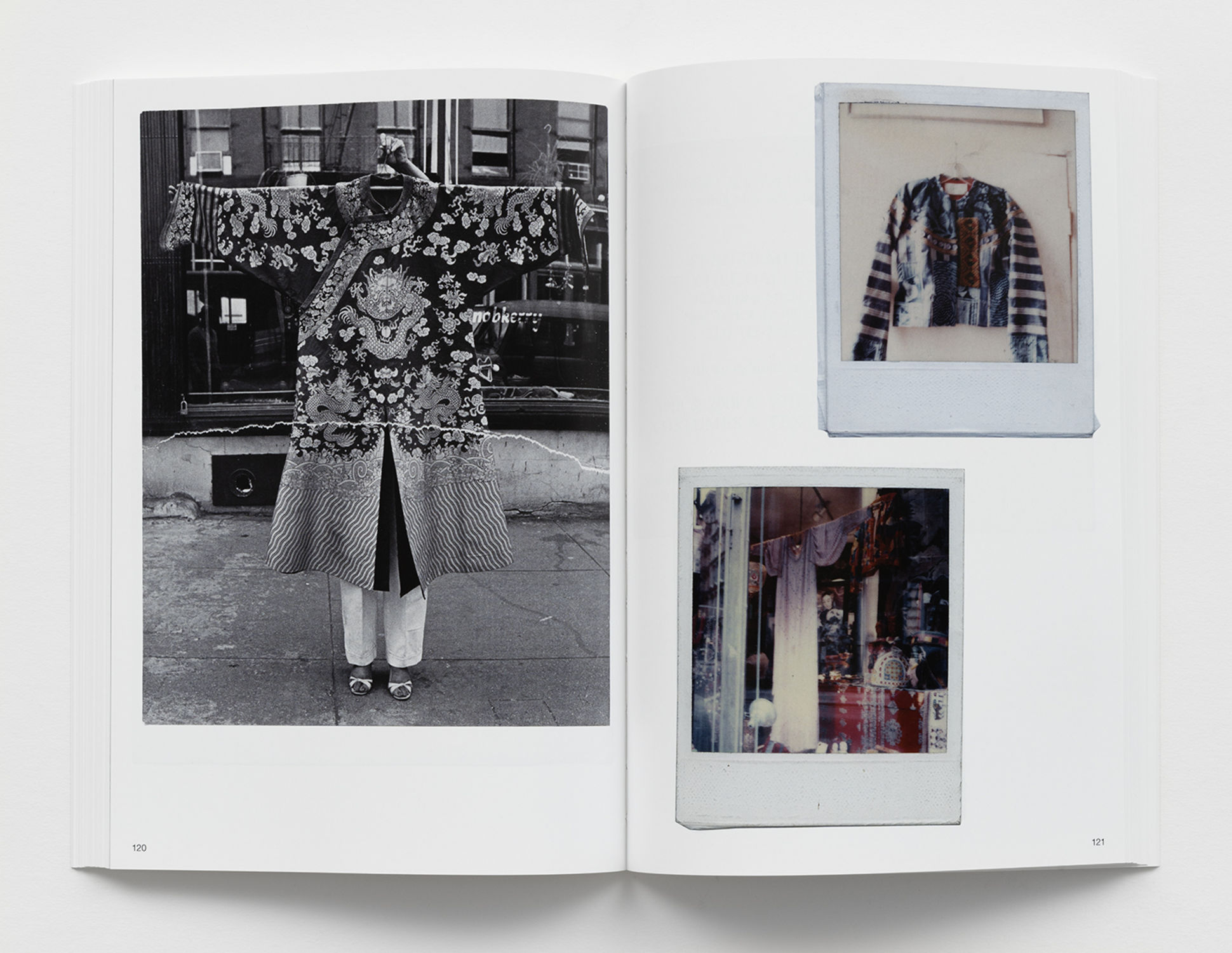

Svetlana Kitto, Sara Penn’s Knobkerry: An Oral History Sourcebook, 2021, installation view SculptureCenter, New York, 2021. Published by SculptureCenter and New York Consolidated. Designed by Pacific. Photo: Charles Benton

Niloufar Emamifar, SoiL Thornton, and an Oral History of Knobkerry brings artists Niloufar Emamifar and SoiL Thornton into proximity with the history of Knobkerry, a store founded and run by artist and designer Sara Penn (1927–2020) in New York City from the 1960s through the 1990s. Foundational to the exhibition at SculptureCenter is a years-long oral history project, conceived and developed by writer and oral historian Svetlana Kitto, that begins to demarcate a potential sphere of influence for Penn, her work, and her store, which was known for its distinctive juxtaposition of clothing, materials, and artifacts, and for Penn’s deep expertise in global and historical textiles. Featuring new work made for the occasion by Emamifar and Thornton, the exhibition as a whole functions as a collaborative form of research between a curator, an oral historian, and artists whose work might be understood in new dimensions were Penn better represented in our recent histories of sculpture, installation, commerce, fashion, and artist-run institutions.

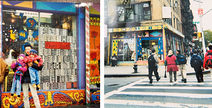

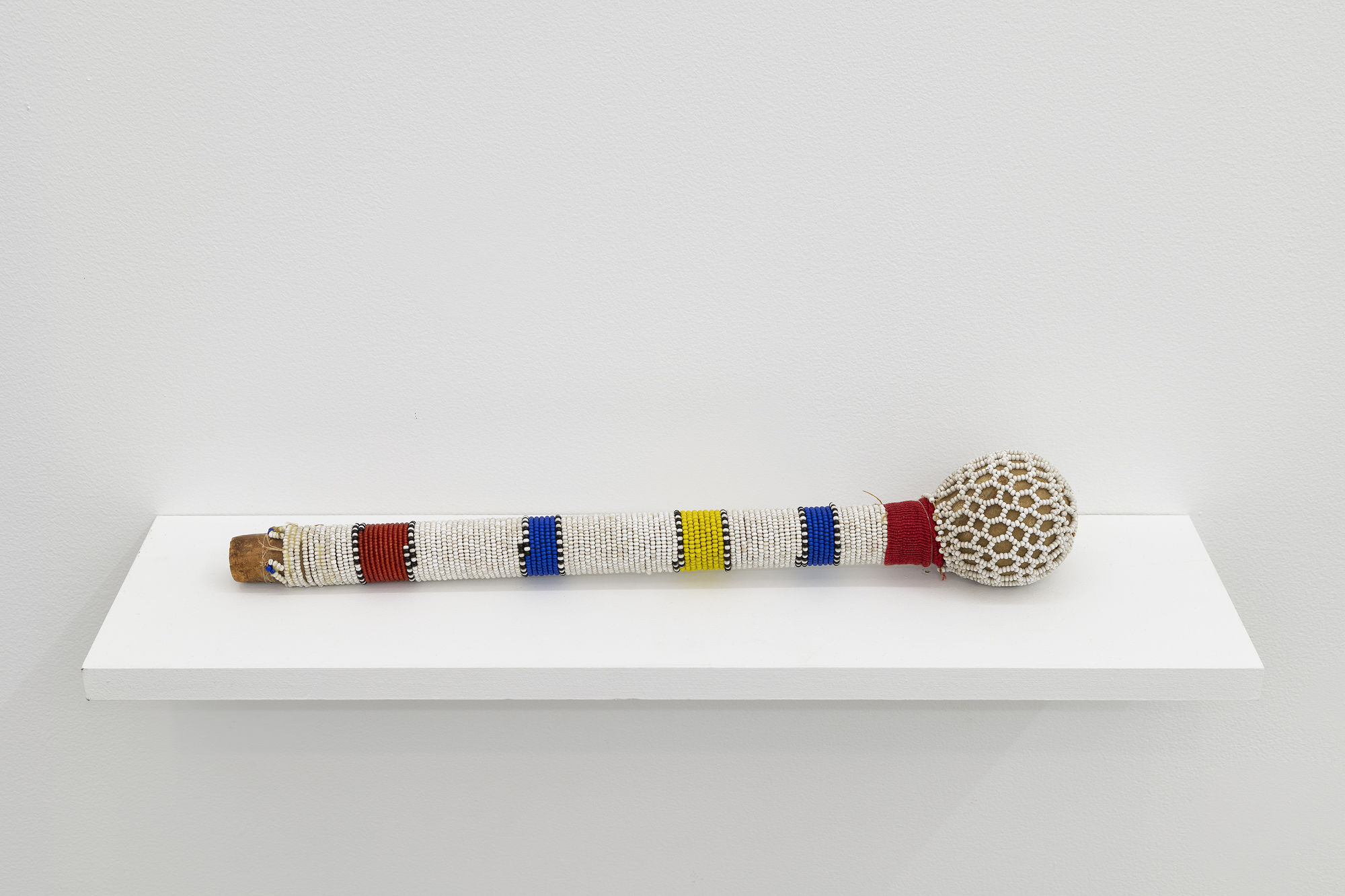

First opened in the East Village during the major social and economic transformations of the 1960s, Knobkerry traded in textiles and ethnographic objects, which Penn expertly transformed into coveted patchwork garments and arranged in elaborate and densely layered displays. In Penn’s hands, these items registered the local effects of globalization, including increased access to objects of international trade, eager markets for fashionable multiculturalism, and a conflicted relationship to American identity. Intimately produced with her singular expertise and craftsmanship, Penn’s work was publicly lauded, circulated, copied, and codified as the archetypal “hippie” style (though Penn referred to Knobkerry’s wares as “Third World Design and Art” in the 1960s) by celebrities and mainstream press outlets. At the same time the store served as an important physical and social space for a network of Black intellectuals, musicians, and artists, and for a broader subset of cultural and subcultural figures passing through New York – even as its brick-and-mortar storefront moved to SoHo and then to TriBeCa, on a now-familiar path of rent crisis and gentrification.

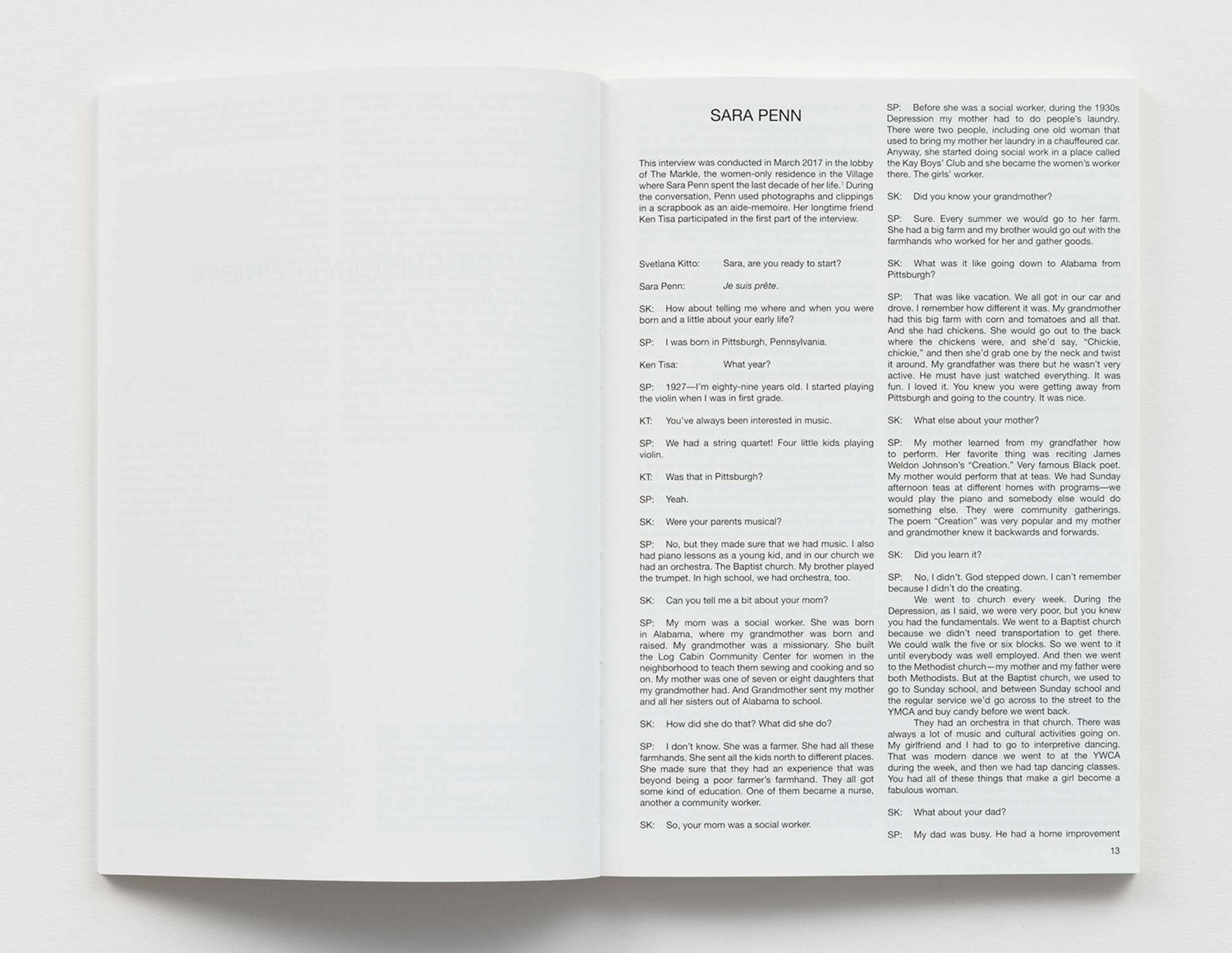

Sara Penn and Knobkerry are represented by a publication that collects fifteen long-form interviews with figures close to Knobkerry, conducted by Kitto between 2017 and 2020. The book also includes extensive reproductions of archival materials related to Penn and the store, collected by Kitto in collaboration with Penn and a number of her close relations. As Kitto and exhibition curator Kyle Dancewicz note, “In lieu of a large physical presentation of Penn’s work or objects that passed through Knobkerry, this exhibition provides a forum for recollections of Penn’s underappreciated artistic and ideological priorities. It looks to her peers to describe the expansive position she occupied and the physical, social, and aesthetic context she largely constructed for herself.”

SoiL Thornton and Niloufar Emamifar will each present new work for the exhibition. Through relatively unstructured methods (Emamifar and Thornton were not prompted to make work directly in response to Knobkerry, for example), the exhibition aims to open a new conversation and propose further engagement with Penn’s legacy—and to evade often overdetermined institutional claims of rediscovery.

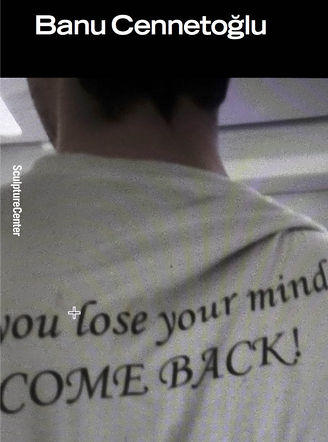

Thornton’s recent sculptural work has engaged the currency of acquired materials, whether store-bought clothing or household supplies. At SculptureCenter, Thornton hangs sculptures of garments: some handmade recollections of milestones in popular fashion, others more or less off the rack, and yet others modeled on a kind of paranoid vernacular performance wear, like the tinfoil Faraday cap. Dressing absent bodies, Thornton’s work looks at fashion and sculpture as related and overlapping disciplines in this context, both operating as open categories for producing a gender gray area that oscillates between more and less legible, and more and less compromised, forms. In the 1960s, Knobkerry envisioned a well-researched new look for the production of an identity outside of American Eurocentric traditions, and then saw the look co-opted into a “hippie” aesthetic for a presumably white audience. Thornton’s work traces a similar, if more uncanny and bizarre, flattening through the use of a Swedish snowsuit emblazoned with the logo “POC” (apparently an acronym for “piece of cake”). Accounts of those close to Knobkerry suggest that Sara Penn’s global design sensibility expressed discontentment with forces of assimilation, white middle-class aspirations, and national identity as pushed against and often rejected by Penn’s circle of Black artists and intellectuals in particular. In a new context, Thornton’s work throws up roadblocks and detours to the public negotiation of identity today, dead-ending, remaking, and resizing garments of a mass culture.

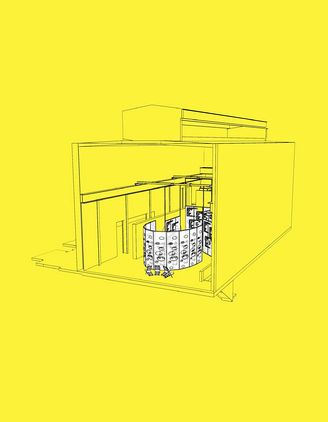

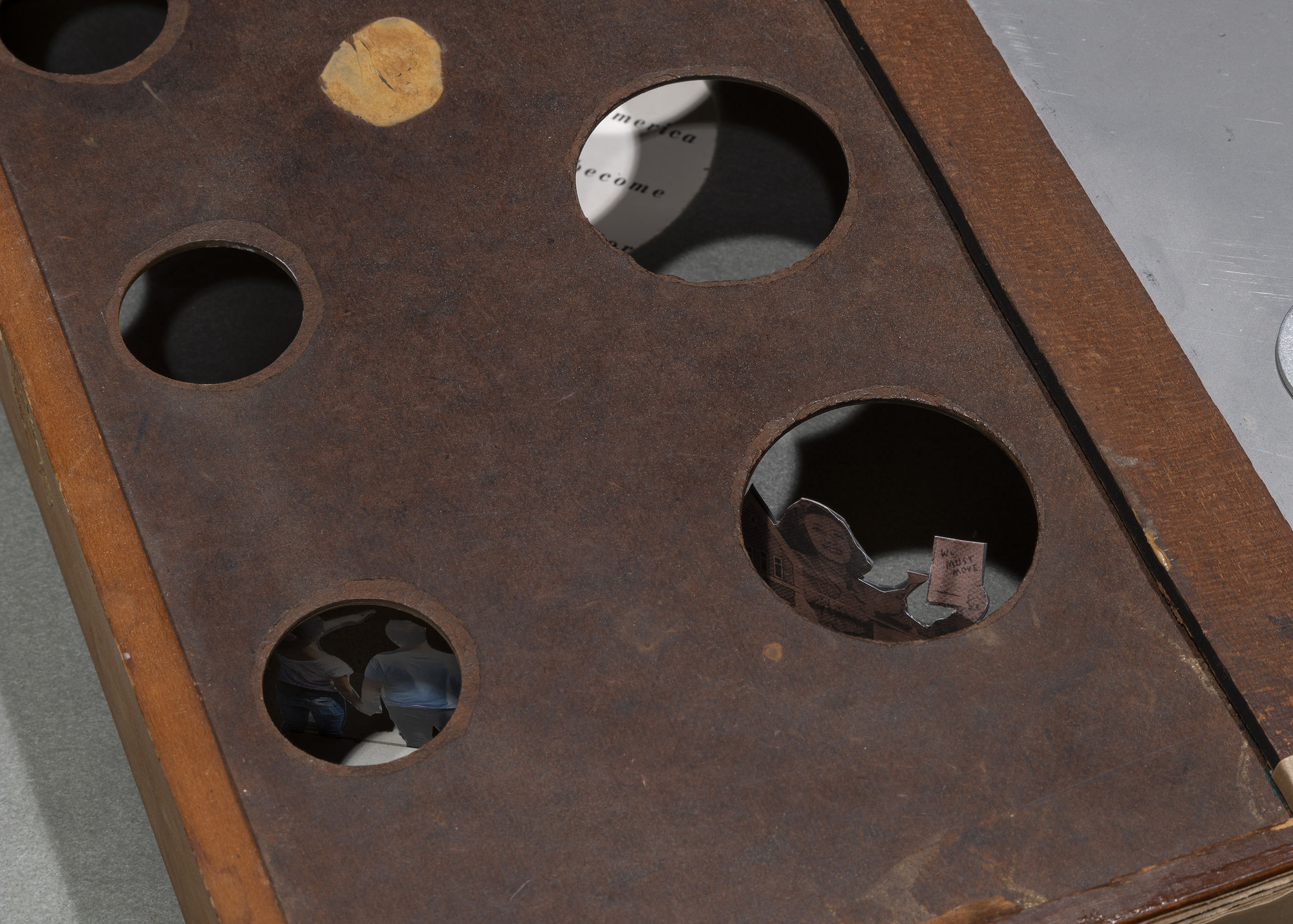

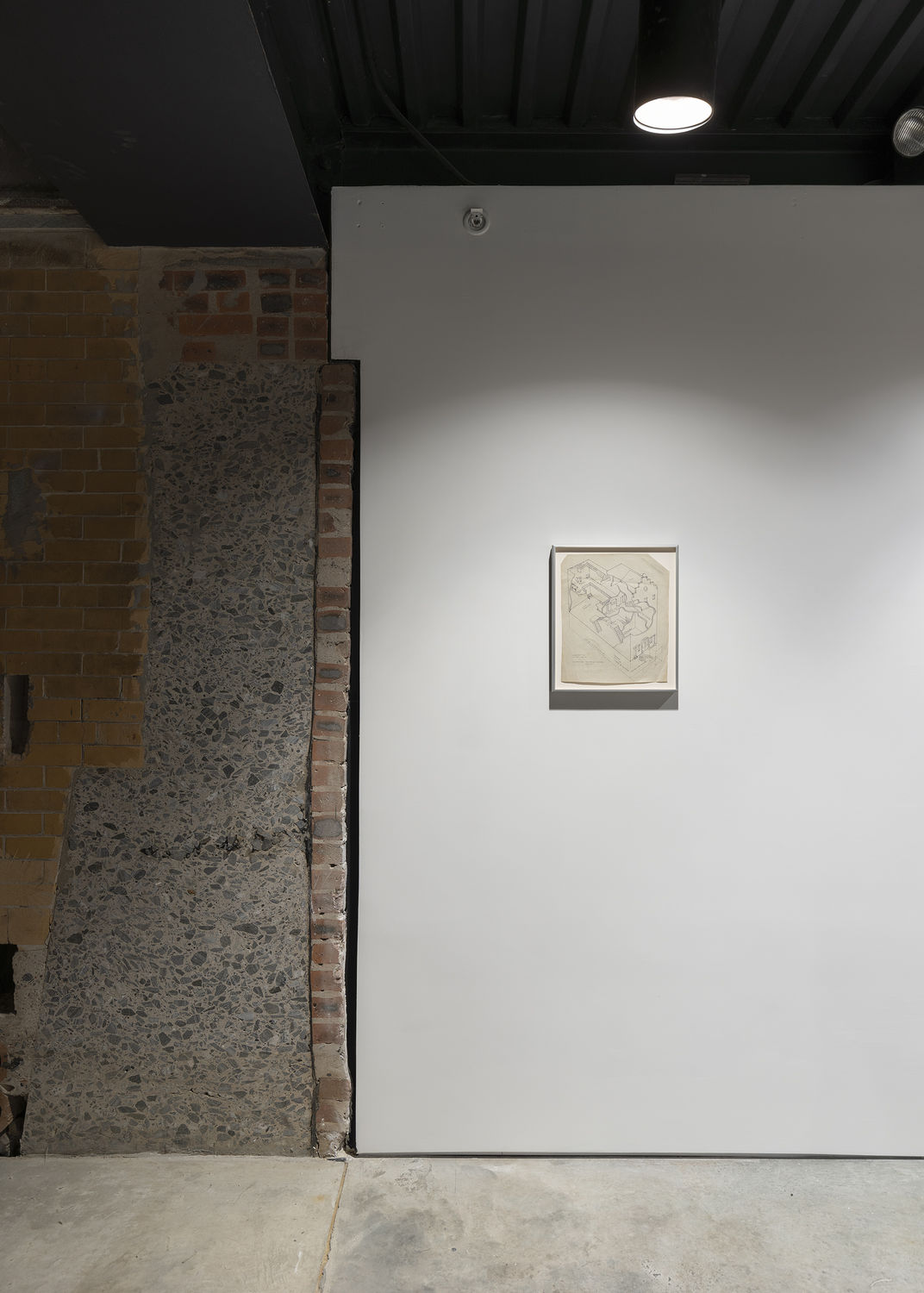

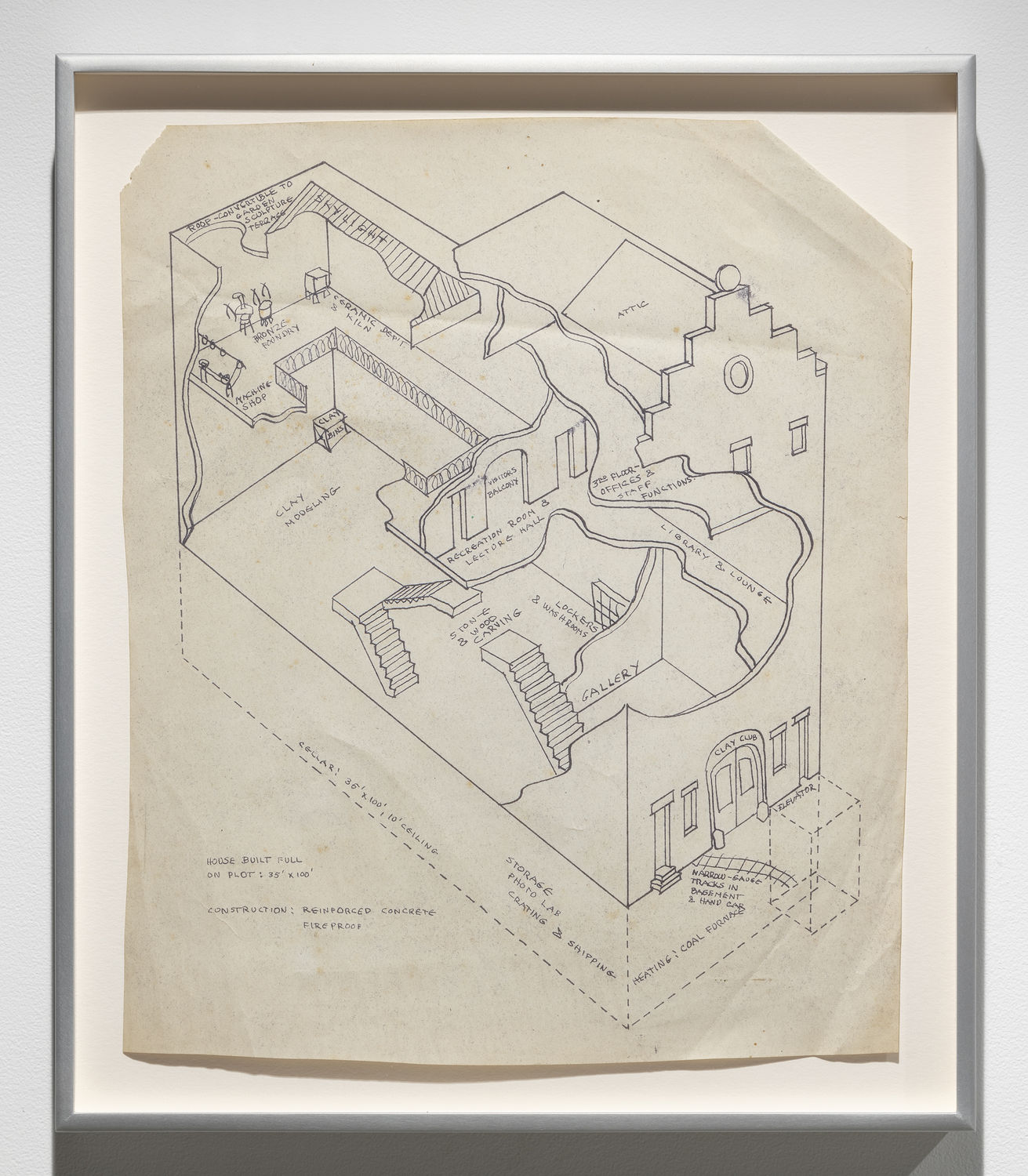

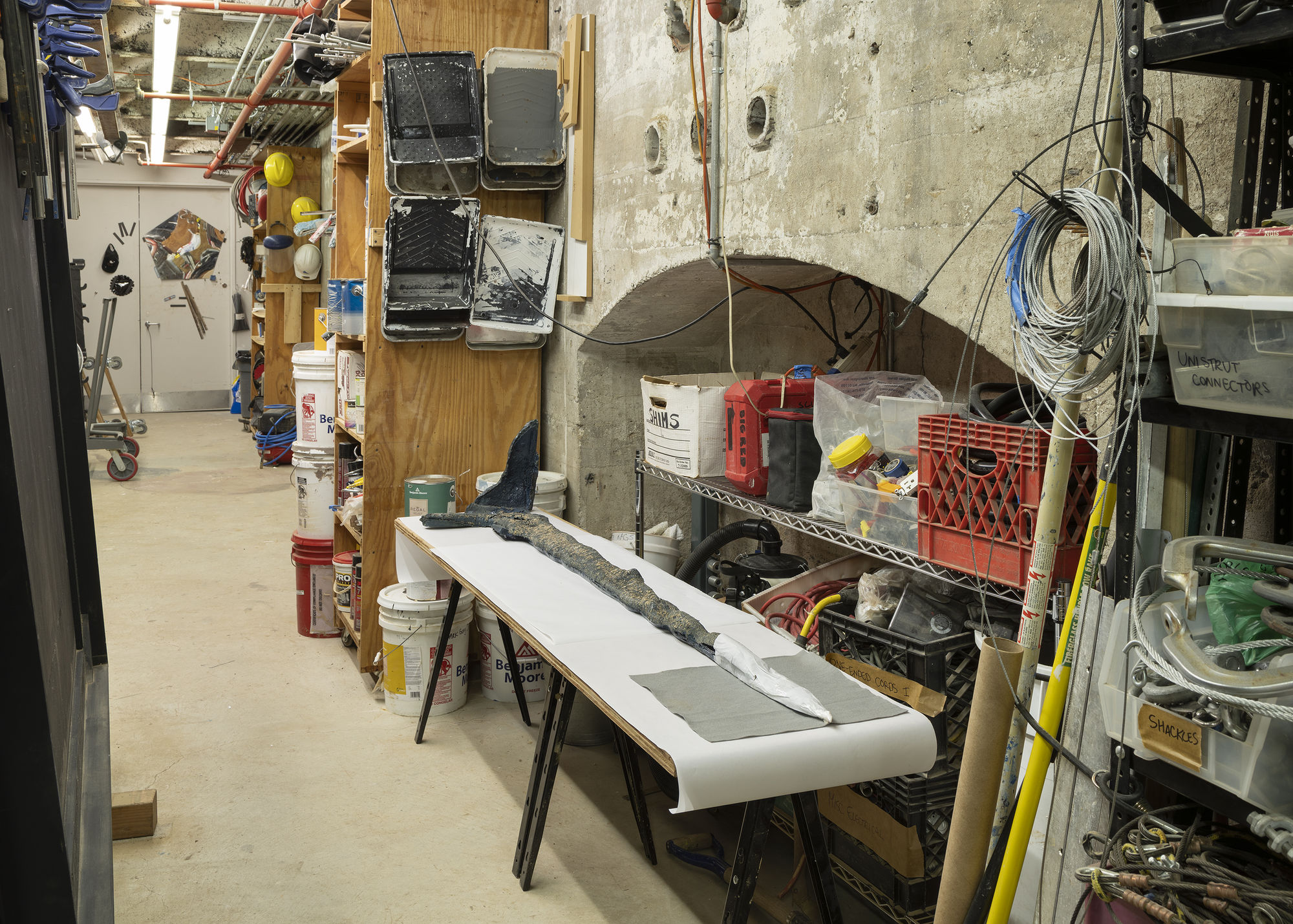

Throughout her practice, Emamifar casts artistic production as an excess of psychically charged architectures of regulation, maintenance tasks, and compromises for how to access, use, and pay for space—and, subsequently, to “freely” express ideas, or to engage in self-determining activities. Emamifar’s project for the exhibition has drawn from SculptureCenter’s disordered archive (from its founding as “Clay Club” in 1928 to its present life) to consider institutional spaces of production and how they reflect the material realities of the artists and artworks with which they engage. As a lens on Emamifar’s concerns, Penn’s pioneering proprietorship, especially as a Black woman in downtown New York in the 1960s, foregrounds what it means to produce a publicly oriented culture outside of direct institutional support, instead utilizing a private commercial form which nevertheless remains prey to the business incentives of commercial real estate rental. Penn’s entrepreneurial vision for global design in the ’60s prefigured a very different ’90s global economy with detrimental storefront-level effects; Emamifar’s work locates the scraps, tensions, and challenges of working within this order today.

Despite the diverging forms of visibility Penn enjoyed at various times in her life, her legacy remains largely unexplored, and Knobkerry has not entered a significant conversation with the artist-run commercial enterprises often invoked to define the socioeconomic-aesthetic whirlwind of 1970s New York. Even now, when the relationship between art, retail, and extra-institutional practices have become more legible, Penn’s contributions are not adequately appreciated. Almost two years after Penn’s death, this exhibition and Kitto’s oral history project offer the time and space to investigate what Knobkerry might mean in retrospect. In this way, the project reflects a new approach to SculptureCenter’s longstanding support of underacknowledged artists and work.

The exhibition is curated by Kyle Dancewicz, Interim Director.

Sponsors

Leadership support of SculptureCenter’s exhibitions and programs is provided by Carol Bove, Jill and Peter Kraus, The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, Lee Elliott and Robert K. Elliott, Eleanor Heyman Propp, Miyoung Lee and Neil Simpkins, Jacques Louis Vidal, Robert Soros and Jamie Singer Soros, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

SculptureCenter’s annual operating support is provided by the Elaine Graham Weitzen Foundation for Fine Arts; the Lambent Foundation Fund of Tides Foundation; the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation; A. Woodner Fund; Libby and Adrian Ellis; The Willem de Kooning Foundation; Teiger Foundation; Helen Frankenthaler Foundation; Cy Twombly Foundation; Arison Arts Foundation; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York State Legislature; and contributions from our Board of Trustees, Director’s Circle, SC Ambassadors, and many generous individuals and friends.