Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995

Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995Sep 17–Dec 17, 2018

- Images

- Text

- Events

- Press

- Sponsors

- Related

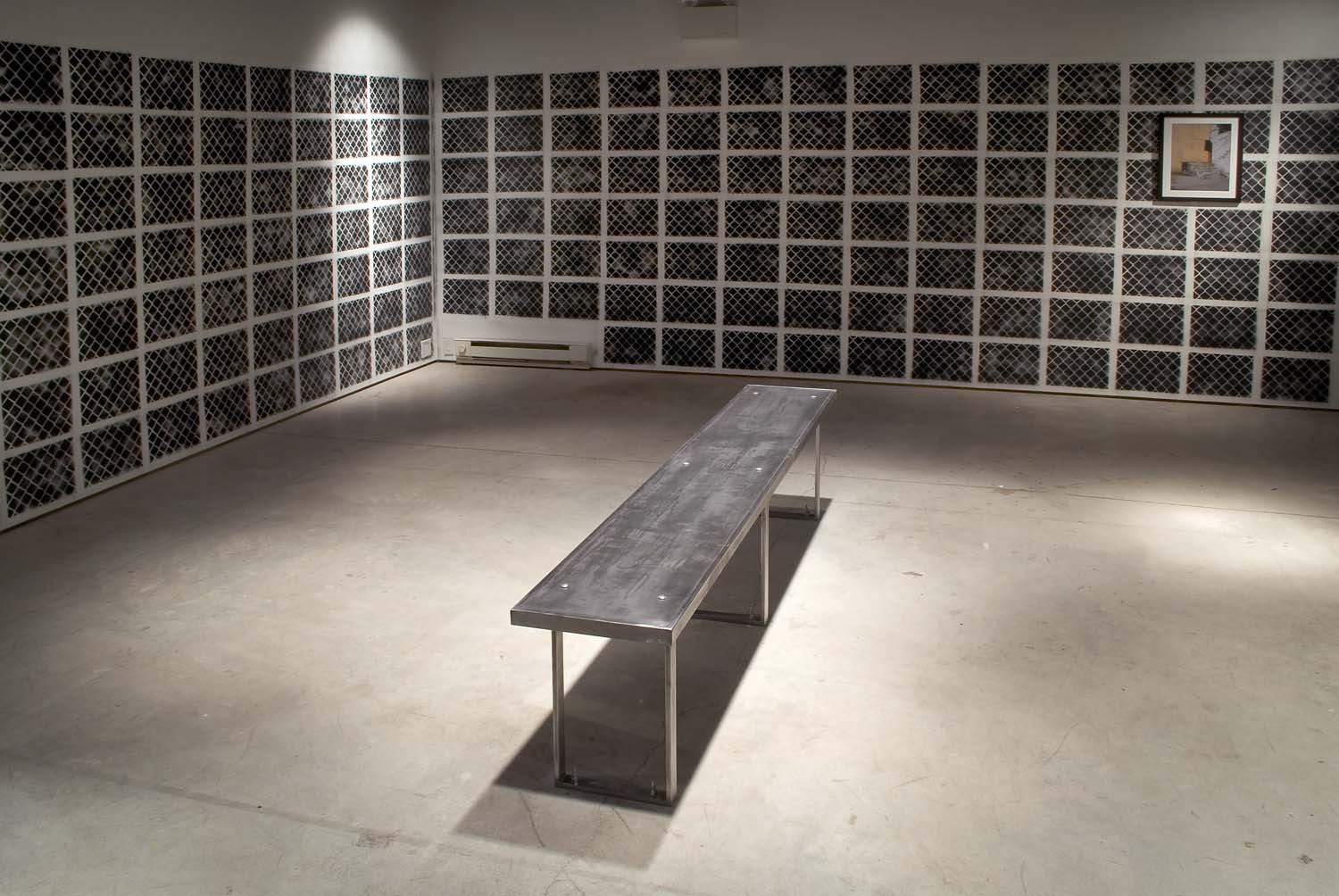

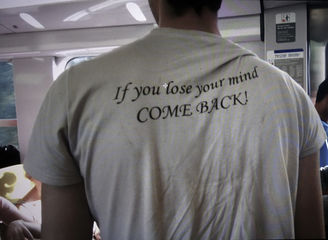

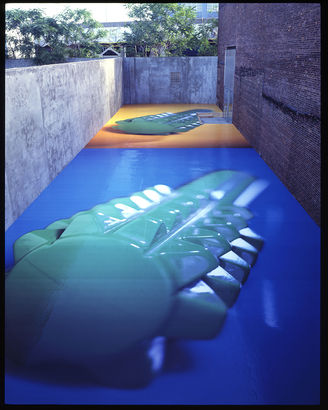

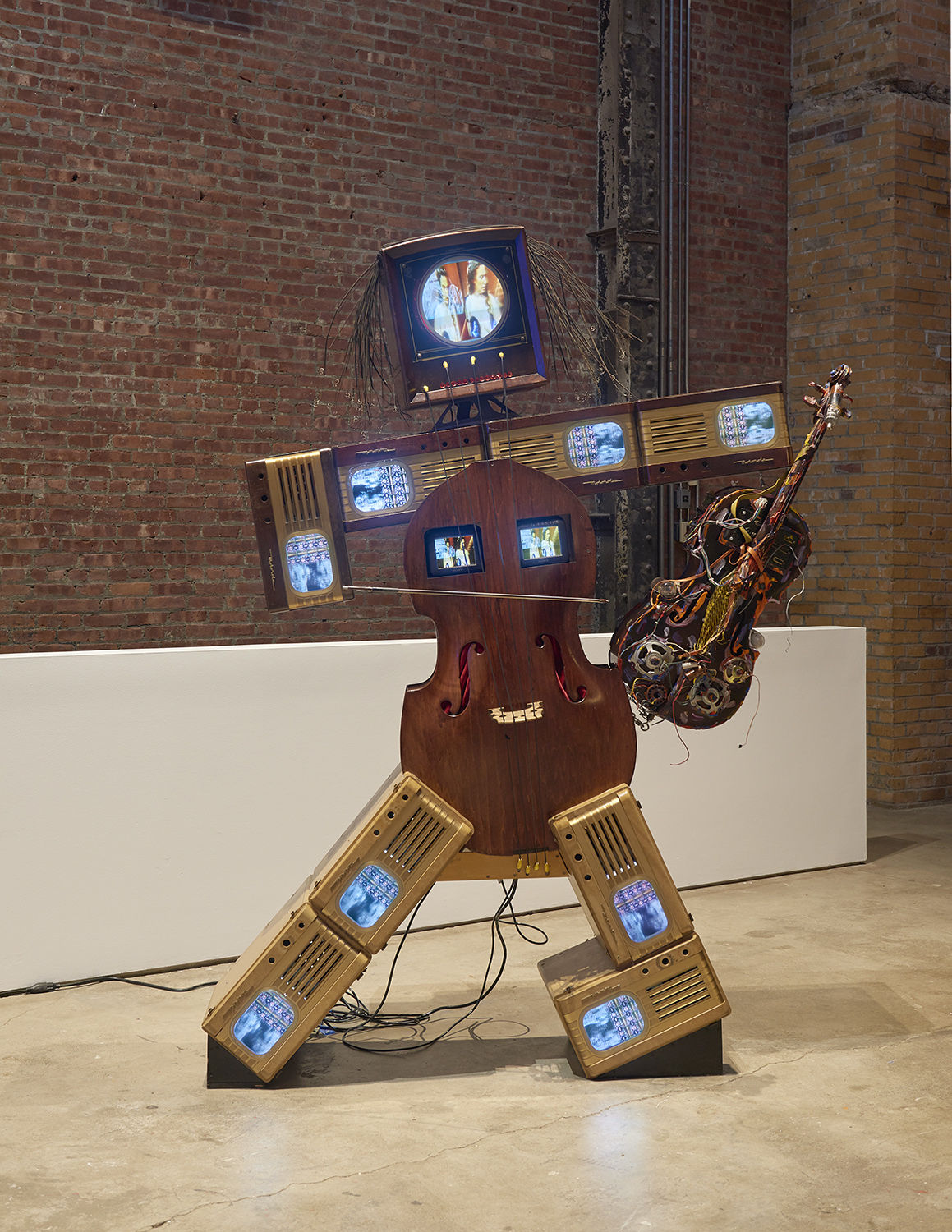

Installation view, Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974-1995, SculptureCenter, New York, 2018. Photo: Kyle Knodell

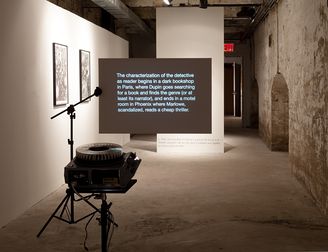

Before Projection shines a spotlight on a body of work in the history of video art that has been largely overlooked since its inception while simultaneously placing it within the history of sculpture. Exploring the connections between our current moment and the point at which video art was transformed dramatically with the entry of large-scale, cinematic installation into the gallery space, Before Projection presents a tightly focused survey of monitor-based sculpture made between the mid-1970s and the mid-1990s.

From video art’s beginnings, artists engaged with the sculptural properties of the television set, as well as the possibilities afforded by juxtaposing multiple moving images. Artists assembled monitors in multiple configurations and video walls, and from the 1980s onward incorporated TV sets into elaborate environments and architectural settings. In concert with technological advances, video editing and effects also grew more sophisticated. These video works articulated a range of conceptual and thematic concerns related to the television medium, the still and moving image, seriality, figuration, landscape, and identity. The material heft of the cube monitor (before the advent of the at-screen) anchored these works firmly in three-dimensional space.

Before Projection focuses on the period after very early experimentation in video and before video art’s full arrival—coinciding with the wide availability of video projection equipment—in galleries and museums alongside painting and sculpture. Proposing to examine what aesthetic claims these works might make in their own right, the exhibition aims to resituate monitor sculpture more fully into the narrative between early video and projection as well as assert its relevance for the development of sculpture in the late twentieth century.

Maria Vedder’s PAL oder Never The Same Color was first presented in 1988. PAL (Phase Alternating Line) is the system used to standardize color broadcasting in Europe, developed for analog television. NTSC (National Television System Committee), mockingly dubbed “Never The Same Color,” is the competing standard in North America. This work consists of a wall grid of twenty-four monitors, with one monitor set aside. Looped on the monitors is historic television color test footage, including a host who presents herself in PAL and then NTSC to illustrate the difference. The video proceeds to test the primary colors of television (red, green, and blue): a “B” for blue appears alongside footage of a sky, a blue rose, and a standard blue screen. Not only does the work nod to different technological systems for calibrating color across cultures, but also their differing symbolic referents. A blue rose, for instance, would have been recognized as the Blue Flower from the German Romantic tradition.

When viewing Dara Birnbaum’s early two-channel video installation Attack Piece (1975), the visitor stands between two monitors facing one another. One monitor shows Super 8 footage shot by four artist collaborators, including Dan Graham. The four successively “attack” a seated and stationary Birnbaum, the cameras recording their aggressive advances towards her. Armed with a 35mm still camera, Birnbaum does not remain idle, as the other monitor shows a series of photographs she captured as the intruders approached. Attack Piece sets out to reclaim the medium for the female filmmaker and her gaze: training her lens onto mainly male camera operators, she complicates distinctions between subject and object, stalker and stalked, attacker and attacked.

Shigeko Kubota’s River (1979–81) is composed of three monitors hung at eye-level above a re ective trough equipped with a wave motor. The monitors alternate footage of Kubota swimming with brightly colored graphic shapes, which were created with state-of-the- art postproduction equipment of the time. Re ected on the surface of the water, the images’ legibility is periodically disrupted by the wave motor. The work typi es Kubota’s recurring interest in water and video as apt mediums to represent cyclicality, as well as her idea of video as “liquid reality.”

In 1964, Nam June Paik made the first “robot” in his series of sculptural assemblages that employ TV monitors to depict figures. That year Paik also met his longtime collaborator Charlotte Moorman, a classical cellist involved in experimental performance. Charlotte Moorman II (1995) depicts his friend with a cello for a torso, monitors for extremities that show footage of Moorman (at times distorted), and wires for hair.

Ernst Caramelle’s Video-Ping-Pong (1974) examines the relationship between the human body and video through a recording of a Ping-Pong match, which plays on two monitors mounted on AV carts at approximately eye level and positioned in front of a “real” Ping-Pong table. Sounds of the bouncing Ping-Pong ball are audible, although no ball is visible between the two monitors. The result is a disarming sense of the players’ presence in the space of the sculpture.

To make Equinox (1979/2016), Mary Lucier recorded seven days’ sunrise from the thirty- rst oor of a building in Lower Manhattan. Each day, she progressively zoomed in on the sun while gradually shifting the camera’s angle northward to follow the sun’s natural movement. And each day, broader marks were “burned” onto the camera’s internal vidicon tube, which manifest on the tape as dark greenish streaks in the sky that trail the path of the sun. The seven consecutive videos showing the accumulated burn marks are presented on a series of monitors increasing in size, each mounted on a tall pedestal.

In her early work Snake River (1994), Diana Thater utilizes three monitors, each displaying footage in one of the three colors (RGB) that together make a full-color image on a CRT monitor. This tactic makes visible the “additive” system of color mixing, highlighting not only technological standards but also the mechanics of visual perception. The monitors feature footage of the American West, whose typical depiction in cinema spectacularizes the land’s vastness as emblematic of freedom, opportunity, and sublimity. Snake River sets out to counter these ideologically-charged representational tropes, as well as the spectacle of video projection, which was starting to gain traction in mid-1990s.

Friederike Pezold is interested in subverting classic dualisms between painter and model, subject and object, as codified in traditions of women’s representation in film, painting, and beyond. Represented here by part of her major video series The New Embodied Sign Language, this sculpture by the same title comprises four monitors displaying close-up videos of the artist’s body altered by theatrical makeup. The videos (subtitled Augenwerk [Eye Work], Mundwerk [Mouth Work], Bruststück [Breast Piece], and Schamwerk [Pubic Work]) are shown on monitors stacked on top of each other to reach roughly the height of a human body.

In Takahiko Iimura’s TV for TV (1983), two monitors are positioned face-to-face, each tuned to a different broadcast station or to static. Their respective streams are only directed toward the other television set, rendering their images nearly invisible to the viewer. The work explores properties unique to video and distinct from film: the medium’s capacity for immediacy and simultaneity. On view in the gallery for months at a time, the work highlights television’s incessant streaming of images in a nonreciprocal, perpetual flow.

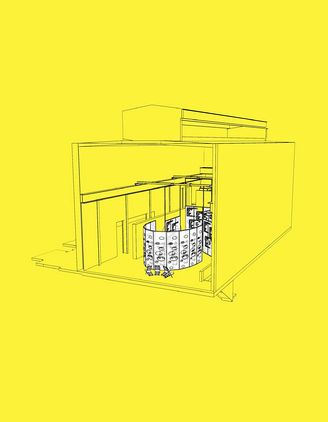

Psychomimetiscape II is one of Tony Oursler’s early monitor- based sculptures, taking the form of what Oursler calls a “model world.” Mounted atop a pedestal, it resembles an architectural model; rendered in somber gray, it depicts a nuclear cooling tower, a medieval- style tower, and a barren landscape. Embedded within are two tiny monitors: one placed at the bottom of a depression in the ground, streaming live-broadcast TV images of reworks, the other located in the tower, playing back an absurdist short narrative employing hand- drawn and computer-generated animation.

In Credits (1984), Muntadas edits together a sequence of credits, such as those found at the end of films and television programs, and displays them in a loop. Foregrounding what the artist has called the “invisible” information underlying mass media productions, Credits considers the features of the credit sequence—typography, size, rolling speed, audio track—as revealing indices of hierarchy and representation. In so doing, Muntadas investigates the ways in which producing institutions choose to represent themselves and how material conditions such as production value, fees, and authorship determine the media landscape.

Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974-1995 is organized by Henriette Huldisch, Director of Exhibitions and Curator, MIT List Visual Arts Center. The presentation at SculptureCenter is organized by SculptureCenter Executive Director and Chief Curator Mary Ceruti with Kyle Dancewicz, Director of Exhibitions and Programs. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue edited by Henriette Huldisch with additional contributions by Edith Decker-Phillips and Emily Watlington, published by Hirmer Verlag in association with the MIT List Visual Arts Center.

Events

Sponsors

Lead underwriting support of SculptureCenter’s Exhibition Fund has been generously provided by the Kraus Family Foundation. The New York presentation of Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974-1995 is made possible with major support by Robert Soros.

SculptureCenter’s programs and operating support is provided by grants from the Lambent Foundation Fund of Tides Foundation; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; the National Endowment for the Arts; the A. Woodner Fund; New York City Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer; and contributions from our Board of Trustees and Director’s Circle. Additional funding is provided by the Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation and contributions from many generous individuals. SculptureCenter’s refreshed brand identity, website design, and online marketing initiatives are supported in part by the LuEsther T. Mertz Fund of The New York Community Trust.